|

Movement and Dance Concepts

in Laban’s (1926) Choreographie (2011) Jeffrey Scott Longstaff Rudolf Laban’s 1926 German publication Choreographie contains an abundance of

concepts that would eventually evolve into modern-day Labanotation and Laban

Movement Analysis. Rudolf Laban

appeared to use this publication as a kind of workbook, introducing a variety

of concepts and methods for notating human body movement, sometimes including

alternative methods designed for the same purpose. An attempt is made here to give an overview of

the German-language concepts in Choreographie

(page numbers refer to the original 1926 publication). Format: Italicized: Non-English

words (German or French) Bold: English

words used in this translation for specific German words in Choreographie Outline

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Dance Writing, Script,

Notation “Choreographie” (Choreography, pp.

19, 54) appears both as the title of the book and also in the titles of

Chapters 7 and 17. This is used in its

original sense as the writing or notating of dance, rather than the

modern-day usage of ‘choreography’ as referring to dance composition. In the

same way musical composition is tied to musical notation with the description

of ‘writing a song’ mean the composing of the song (whether it was actually

written down or not).

concept (Begriff;

p. 84) (ie. idea) conception (grifflich; p. 93) conceptual (begrifflich; p. 84) conceived (begriffen; p. 76) movement-concepts (Bewegungsbegriffe; title chapter 27) spatial-direction-concepts (Raumrichtungsbegriffe; p. 8) time-concepts (Zeitbegriffe; p. 84) auxiliary-concept (Hilfsbegriff; p. 84) The method for representing these dance concepts

is explored through the creation of various dance notation, dance writing, or

dance script. These three concepts are

used almost interchangeably and could receive the same English translation. The idea of a dance “script” was often used by

Laban (1954, 1955) in his English writings, and the idea of “dance writing”

is also commonly used (Preston-Dunlop & Lahusen, 1990). Therefore both of

these English translations of “script” (Schrift), and “writing”

(schreiben) are maintained in this translation in preference to what

might be the more typical English concept of “notation” (Notierung)

which is also used in Choreographie,

but only rarely: notation / notate (Notierung / notieren; pp. 76, 101) musical-notation-script (Musiknotenschrift; p. 85) (using both “notation” and

“script”) dance-notation (Tanznotierungen; p. 81) script (Schrift;

pp. 39, 54, 63, 73, 92, ...etc.) ballet-script (Ballettschrift, p. 63) dance-script (Tanzschrift; pp. 12, 21, 64) movement-script (; p. 14) musical-notation-script (Musiknotenschrift; p. 85) diagonal-script (Schrägenschrift; p. 32; Schrägschrift; p. 103) script-signs (Schriftzeichen; p. 102) column of script (Schriftreihe; p. 102) - a column of writing. script-series (Schriftreihe; p. 101) script-picture (Schriftbild; p. 101) trial-script (Schriftversuch; pp. 20, 69, 96, 103) script-guidelines (Schriftanleitung; Title appendix II, p. 100) write (schreiben;

pp. 92-93, 101, 102) writes (schreibt; p. 4) ) (ie. to describe, to

draw) written (geschreiben; pp. 92, 98-99, 101-103) written (ausgeschreiben; p. 96) (Lit. written-out) write-out (aufzuschreiben; p. 100) ballet-writing (Ballettbeschreibung p. 63) writing-possibilities (Schreibmöglichkeiten; p. 103) describe / description

(beschreiben; pp. 6, 8-10, 54, 57, 59, 62, 65) (uses same

German root “schreiben” - to write) Dance and movement is represented in notation or

script with various signs or symbols. The English use of either ‘sign’ or

‘symbol’ may vary widely. Works in

Labanotation sometimes refer to “symbols”, such as the “direction symbols”

(Hutchinson, 1970), but the most widespread use refers to “signs” (Knust,

1979a,b; Hutchinson, 1970, 1983) and so has been followed here.

sign (Zeigung

/ zeichen; pp. 54, 65, 67, 69, 102, ...) [cf. ‘signify’] signify

/ signified (Gekennzeichnet; p.55 / kennzeichen;

pp.100-101/aufgezeichnet; p.98) script-signs (Schriftzeichen; pp. 47, 102) spatial-signs (Raumzeichen; p. 85) free signs (title Chapter p.89) timing-signs (Zeitzeichen; p. 85) Starting-sign (Anfangzeichen; p. 47) Ending-sign (Schlußzeichen; p. 47) performance-signs (Vortragszeichen; p. 102) direction-signs (Richtungszeichen; p. 103) dimensional-signs (Dimensionalzeichen; p. 100) diagonal-signs (Schrägezeichen; p. 100) deflection-signs (Ablenkungszeichen; p. 102) position-signs (Positionszeichen; p. 63) movement-signs (Bewegungszeichen; p. 19) pathway-signs (Wegzeichen; p. 102) suspended-leg-signs (Schwebebeinzeichen; p. 95) foot-sign (Fußzeichen; p. 55) leg-sign (p. 95) variation-signs (Variationszeichen; p. 55) prefix-

and secondary-signs (Vor- und Nebenzeichen; p. 102) rhythmic

signs (rhythmische Zeichen; p. 102) (also p.

16) secondary-stream-signs (Nebenströmungszeichen; p. 102) intensity-signs (Intensitätszeichen; p. 102) linking-sign (Bindezeichen; p. 69) lifting signs (high movement) (p. 91) representation (Zeichnung, p. 67) [similar to zeichen - sign] drawing (Zeichnung) pathway-drawing (Wegzeichnungen, p. 62) ground-plan-drawing (Grundrisszeichnung; pp. 65, 102) movement-representation (Bewegungsaufzeichnung; p.

100) dance-representation (Tanzaufzeichnung; pp. 19,

56) terminology (Bezeichnungen;

p. 80) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Body Organization A basic distinction is made between the standing

or supporting leg versus the gesturing or working leg (pp. 92-93). For the

standing leg, two similar German words, “stehen” (to stay) and “Stand”

are both used, and both German terms have been translated as “stand”: stand (stehen

/ steht; pp. 87-88, 96, 101) standing-leg (Standbein;

pp. 87-88, 92-93) [cf. ‘suspending-leg’] standing-leg-exchange (Standbeinwechsel; p. 92) The gesturing leg is identfied through several

different concepts, the most frequent of these is translated as “Suspended” (Schwebend). This

term seems to be used for two different concepts, in one case it is used to refer

to sagittally deflected diagonals (see ‘deflections’) while in this case it is

used to specify the limb which is gesturing. Other concepts of gesture, striving and swinging

are only occasionally used to refer to the limb: suspended [as gesturing

limb] (Schwebend; pp. 10, 59, 68, 86-87) suspending-limbs (Schwebeglieder; p. 100) suspended-leg (Schwebebein; pp. 68-69, 92-93, 101) [cf. ‘stand’] suspending-leg-gesture (Schwebebeingeste; p. 69) suspended-leg-signs (Schwebebeinzeichen; p. 95) gesture (geste) leg-gesture (Beingeste; p. 87) used only once striving (Strebung) usually used to refer to spatial actions or numbers of

movement. bodily-strivings (Körperstrebungen; p. 102): striving-limb (Strebeglied; p. 87) striving-arm (Armstrebung; p. 96) striving-arm (Strebearm; p. 87) striving-leg (Beinstrebung, Strebebeins; pp. 67-68) swinging (Schwung) usually used to refer to spatial

actions or directions swinging-limbs (Schwunggleidern; pp. 17, 19). swinging

body-quarters (schwingenden Körperviertel; p. 17) Several concepts describe the “body” (Körper; pp. 68, ...

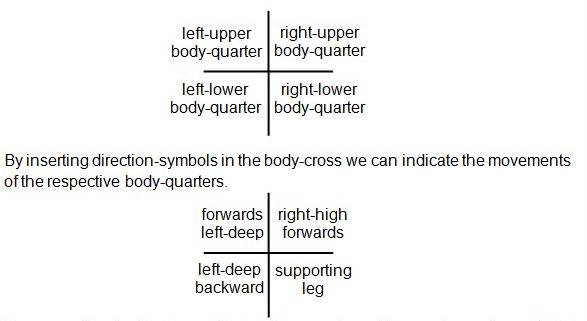

etc.), including: body-part (Körperteil; p. 86) body-side (Körperseite; pp. 64, 74) body-construction (Körperbaues; p. 24) In Choreographie the body was represented

graphically with the “body-cross”

(Körperkreuz; p. 15), later as the referred to as the “spatial-cross”

(Raumkreuz; pp. 89, 103). Each of the “body-quarters”

(Körperviertels; pp. 15, 17 ...etc.) were indicated within one quarter

of the cross, overall giving an idea of the body positions or “body-situations” (Körperlagen;

pp. 17 ...etc.)

(Laban 1926, p. 15) . A few times the body action of a weight transfer

is described as an exchange of weight: exchange (of weight) (Wechsel;

wechseln; pp. 33, 68, 75-76, 92) standing-leg-exchange (Standbeinwechsel; p. 92). In a couple places Laban seems to have created a

concept to describe limb organisation, which he identifies as being similar

to fingering (Fingersatz), such as

used to refer to the organisation and employment of the different fingers

when playing a piano. He creates a

comparable concept for the limbs of “Gliedersatz” which has no obvious

translation in English (Satz can be

a phrase or a sentence) but has been translated here as “limb-sequencing” since this concept is often used in body study

to describe the coordination within a limb and amongst different limbs: sequencing (used as a

gerund-noun) (Satz; pp. 14, 100) [ie. sequencing of body parts] fingering (Fingersatz; p. 89) [organizing finger motions to play an

instrument] limb-sequencing (Gliedersatz; pp. 89, 100) [a word created by Laban similar to

fingering] The same English word sequencing is also translated from the German “Folge” in other places when referring

to a sequence of movements or a spatial

sequence, but in the case of “Satz”

it refers to body-sequencing. The idea of “Connection”

(Verbindungen / verbunden) while many times used to refer to

‘connections’ of spatial lines and points (pp. 8, 15, 22, 36, 40, 43, 49) is

also used many times to refer to organisation or integration amongst body

parts (pp. 8-9, 11, 14, 19, 73, 87). Similarly in one place Laban describes how

full-body connections reveal “integrated” (einheitliche; p. 19)

body postures. This perspective is

obviously a similar concept to the modern-day Laban Movement Analysis idea of

bodily “integration” and “connectivity” (Bartenieff & Lewis, 1980;

Hackney 1998). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

At one point Laban offers a detailed account of

possibilities for full-body organizations, referred to as “limb-correlations” (Gliederzusammenhängen; pp. 86-87). The German zusammenhängen would be literally translated as

“hanging together” and in Choreographie

it is usually used to describe correlations and harmonic laws amongst spatial

pathways (see “Transformations” below).

However here the same “correlations”

(zusammenhängen) concept seems to be applied to body organisation and

might be considered as an early form of what is considered to be the “body”

area of modern-day Laban Movement Analysis Laban (pp. 86-87) uses four factors to decipher

basic “limb-correlations”: Limb: Upper limb Lower

limb Limb action “streben” (“striving”) ie.

impetus of motion (see “movement” below) “schweben”

(“suspending”) ie. “maintaining the

countermovement” (pg. 87) Side of the body into which the limb is moving: “eigenseite”

(“own-side”), “fremdseite” (“foreign-side”) “gegenseite” (“counter-side”) Direction a

limb moves into its own up / down direction: “nach” (to, towards) seems to imply: upper

limb moves upwards lower limb moves downwards a

limb moves into the opposite up / down zone: “nach

unten” (“downwards”) upper limb moves downwards “nach

oben” (“upwards”) lower limb moves upwards

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Limb |

Action |

Direction |

Side of body |

|||||||

|

a) |

Upper limb |

Strives |

[ Upwards ] |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Suspends (countermovement) |

[ Downwards ] |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

b) |

Upper limb |

Strives |

[ Upwards ] |

Foreign-side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

[ Downwards ] |

Foreign-side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

c) |

Upper limb |

Strives |

Downwards |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

Upwards |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

d) |

Upper limb |

Strives |

Downwards |

Counter-side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

Upwards |

Counter-side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

e) |

Upper limb |

Suspends (countermovement) |

[ Upwards ] |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Strives |

[ Downwards ] |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

f) |

Upper limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

[ Upwards ] |

Foreign-side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Strives |

[ Downwards ] |

Foreign-side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

g) |

Upper limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

Downwards |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Strives |

Upwards |

Own side |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

h) |

Upper limb |

Suspends

(countermovement) |

Downwards |

Counter-side |

|||||||

|

|

Lower limb |

Strives |

Upwards |

Counter-side |

|||||||

|

Body organisation, especially reflex reactions to

maintain equilibrium with countermovements

is closely associated with spatial symmetry and Laban’s concepts of

laws of harmony. This is described in

more detail below (see “symmetry”). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Series and Clusters An explicit distinction is made between the

sequential, progression aspects of movement and the simultaneous, configurational

aspect of momentarily held positions (pp. 90-91). The sequential aspect of movement is usually

considered to be a series (Reihung; reihen), though once

as series (from the French Serie) and a very similar concept,

translated as sequence (Folge) is also frequently used. Several

times the two German terms are even joined together as Reihenfolge,

this series-sequence redundancy attempted in the English translation of specific-sequence: series (Serie; p. 87 from French) series (Reihung;

reihen; pp. 88-91) form-series (Formreihung; p. 89) specific-sequence (Reihenfolge; p. 25-28, 47, 61) (ie. “series-sequence”) sequence (Folge;

pp. 10-12, 40, 68, 88-89, 101) [ie.

sequence of spatial directions] scale-sequence (Skalenfolge; p. 73) ring-sequence (Ringfolge; p. 39) four-ring-sequence (Vierringfolgen; p. 40) turning-sequences (Wendefolgen; p. 70) specific-sequence (Reihenfolge; p. 25-28, 47, 61) movement-sequence (Bewegungsfolge; p. 11) Simultaneous attributes of movement such as

configurations of body parts are distinguished as “clusters” (Ballung;

pp. 78, 90-91, 101) which implies a pulling or pressing together into a ball

or bale. This could be translated as “configuration” but “clusters” is suggested by

Preston-Dunlop (1981, pp. 49-50) to refer a harmonious relationship of

several spatial elements as “belonging together” and so this seems like an

apt translation here. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Position, Placement, Posture Several concepts are used in Choreographie. which could all potentially be translated

as “position”, the three most frequently used being Position, Haltung

and Stellung. If Laban intends

a significant difference between the concepts it is not clear, and in some

cases they seem to be used almost interchangeable, for example, ‘Beinposition’

(leg-position) is used in one

place followed by ‘Beinhaltung’ in the very next sentence (p. 11). Separate English translations are made for each

of these German terms in an attempt to retain their distinctive characters. ‘Position’

is translated from Position which may indicate a more static quality. Haltung

could also be translated as “position” but it implies a more expressive

action and is sometimes used in German to describe a way of thinking, whereas

Position is not. A halt implies a previous activity just before

stopping the movement whereas position does not imply any previous

movement. Haltung can also imply an entire arrangement of body-parts

and so it is translated here as ‘posture’. This application of

‘posture’ to a single limb, as in “arm-posture”

might seem unusual in English, but it does fit the common definition of

posture as: “a position or attitude of the limbs or body” (Collins, 1986) and

so is used here in the attempt to distinguish the concepts of Position

and Haltung. Likewise, the German Stellung, could also

be translated as ‘position’, coming from stellen, meaning ‘to put’ or

‘to place’. The concept of ‘placement’ in ballet (ie. placing the body

into organised arrangements) is similar to Laban’s discussion of Stellung

(eg. p. 17) and so it has been used as the translation here (though on some

occasions to fit the context of the sentence it is translated as formation. Other similar concepts are also used: position (Position;

pp. 6-8, 35, 44, 54, etc...) ballet-positions (Ballettpositionen; p. 35) leg-position (Beinposition; p. 11) contrary-position (Kontraposition; pp. 10, 19, 27-28, 35) [See

‘countermovement’] position-signs (Positionszeichen; p. 63) false-position (Falschposition; p. 20) (ie. like a “false note” in music, out

of harmony) posture (Haltung;

pp. 7-9, 69, 77, 83, etc...) (eg. “a

stop”) leg-posture (Beinhaltung; p. 11) body-posture (Körperhaltung; pp. 3, 77) postural-stillness (Stillstandshaltung; p. 77) specialized postures (besondere Haltungen; p. 93) placement (Stellung;

pp. 7-8, 17, 77, 83) [cf. ‘formation’] placement (Einstellung;

pp. 1, 3, 75) directional-placement (Richtungseinstellung; p. 1) basic-placements (Grundstellungen; p. 8) hand-swing-placements (Schwunghandstellungen; p. 73) starting-placement (Anfangsstellung; p. 99) end-placement (Endstellung; p. 99) formation (Stellung; pp. 60, 86) portrayal (Darstellung; pp. 60, 62) situation (Lage;

pp. 13, 17, 19, 25-26, 34, 40-41, 84, 100) spatial-situation (Raumlage; pp. 10, 13-14, 100) basic-situation (Grundlage; pp. 24, 100) diagonal-situation (Schrägenlage; p. 25) four-ring-situation (Vierringlagen; pp. 38, 40) three-ring-situation (Dreiringlagen; p. 41) condition (Zustände; pp. 1-3, 17, 74-75) (from ‘stand’) stationary-conditions (Zustande; pp. 2-3) condition-transformations (Zustandswandlungen; p. 1) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Movement, Swinging,

Striving, Leading The most frequently used motion concepts in Choreographie

are ‘movement’ (Bewegung), ‘striving’ (Strebe), ‘swing’

(Schwung), and ‘leading’ (Führung). The most common term

movement (Bewegung) and its shorter form moving, or mobile

(Bewegte) are used in over thirty compound words: movement (Bewegung;

pp. 63, 83, 76, 80, 86, etc....) defense-movement (Abwahrbewegung; p. 83) fighting-movements (Kampfbewegungen; p. 34) artistic-movement (Kunstbewegung; p. 81) kind-of-movement (Bewegungsart; p. 12) [ie.

general ‘kind’, cf. ‘movement-manner’] movement-atrophy (Bewegungswerkummerung; p. 81) movement-expression (Bewegungsausdruck; pp. 63, 80) expressive-movements (Ausdrucksbewegungen; pp. 19, 25) specialized-movement (Sonderbewegung; pp. 73, 93) movement-picture (Bewegungsbildes; p. 100) movement-processes (Bewegungsvorganges; p. 55) movement-manifestations (Bewegungserscheinungen; p. 64) hand-movements (Handbewegungen; p. 73) movement-concepts (Bewegungsbegriffe; title chapter 27) [ie. effort or space concepts] movement-contents (Bewegungsinhalte; p. 80) [ie.

effort] movement-nuances (Bewegungsnuancen; p. 80) [ie.

effort] movement-manner (Bewegungsart; p. 62)

[ie. effort] movement-form (Bewegungsform; pp. 62, 80) [ie. space] movement-progression (Fortbewegung; pp. 62, 65) movement-development (Bewegungsablaufes; p. 64) movement-combinations (Bewegungskombinationen; p. 55) movement-centre (Bewegungszentrum; p. 39) movement-cluster (Bewegungsballung; p. 101) movement-sequence (Bewegungsfolge; p. 11) countermovement (Gegenbewegung; pp. 6-7, 11, 59, 84, 86-87, 98) countermovement-direction (Gegenbewegungrichtung; p. 87) movement-kinesphere (Bewegungsumraums; p. 21) movement-area (Bewegungsfeld; p. 62) movement-script (; p. 14) movement-signs (Bewegungszeichen; p. 19) moving, or mobile

(Bewegte; pp. 4, 10, 14, 29, 58, 60, 68, 74) moving-towards (hinbewegetm; p. 18) move-across (hinüberbewegt; p. 60) arousal (from the same

German root: bewegtheit; p 85) Movement is also frequently described as “striving”

(streben) implying an inner desire and motivation to move. The German

noun Strebe can refer to a brace, a strut, or a pole which supports a

tent, long structures on suspension bridges, or poles on which plants grow

upwards. Translating “striving” into an English noun may be slightly awkward

but this conveys the intention and quality of the German verb ‘to strive’ and

this translation has been attempted here: striving (Strebung,

strebt; pp. 15, 21, 34, 70, 86-87) (ie. an intentional movement) bodily-strivings (Körperstrebungen; p. 102): striving-limb (Strebeglied; p. 87) striving-arm (Armstrebung; p. 96) striving-arm (Strebearm; p. 87) striving-leg (Beinstrebung, Strebebeins; pp. 67-68) spatial-strivings (Raumstrebungen; p. 6): aimed-towards-the-striving (Zielstrebig; p. 34) diagonal-strivings (Schrägenstrebungen; p. 28) equilibrium-strivings (Gleichgewichtsstreben; p. 5) wide-striving (Weitestreben; p. 75) striving-direction (Streberichtung; pp. 78, 86) number

of phases (strivings) within a movement sequence: one-striving (einstrebige; p. 4) multi-striving (vielstrebige; p. 4) two-striving (zweistrebige; p. 4) three-strivingness (Dreistrebigkeit; p. 17) four-striving (vierstrebige; p. 4) five-striving (funfstrebige; p. 4) six-striving (sechsstrebige; p. 4) twelve-striving (zwolfstrebige; pp. 4) secondary-striving (Nebenstrebungen; p. 70)

(see ‘Effort’) In the choreutic tradition, movements have also

been traditionally considered as “swings” (schwung). Principal

of these are the “swing-scales” where movements are “swung-together”

in longer sequences: swing (Schwung;

pp. 12, 17, 24, 34, 48) swinging-movement (Schwungbewegung; p. 65) swing-lines (Schwunglinie; p. 71) central

swings (zentral geschwungen; p. 28) principle-swings (Hauptschwunge; pp. 28, 36, 101) falling-swing (Fallschwung; p. 68) swung-together (zusammenschwungen; p. 49) Bodily

swings hand-swing-placement (Schwunghandstellungen; p....) swinging body-quarters (schwingenden Körperviertel; p. 17) swinging-limbs (Schwunggliedern; pp. 17, 19) (ie. gesturing-limbs) swing-scales (Schwungskalen; pp. 65, 93, 101) high-swing (Hochschwung; pp. 24-25) deep-swing (Tiefschwung; pp. 24-25) outwards-swing (Auswartsschwung; p. 25) [cf. ‘sideways’] inwards-swing (Einwartsschwung; p. 25) backwards-swing (Rückschwung; p. 25) [cf. ‘rearward-thrust’] forwards-swing (Vorschwung; p. 25) [cf. ‘forward-thrust’] Two less easily translatable concepts combine ‘schwung’ with the prefixes ‘An-’ or ‘Aus-’. These are rarely used but they appear to be significant

concepts since they are used within statements on fundamental ‘laws’ of body

organisation in relation to space. The German prefix ‘Aus-’ (literally;

‘out’) is not ‘outward’ in the sense of spatially outward, away from the body

(see list above, Laban uses inwards-swing

and outwards-swing for swings in

and out relative to the body). Instead

‘Aus-’ is added to verbs to indicate that their activity is completed

or fulfilled, ‘carried out’, ‘acted out’, or ‘let out’ and expressed. For

example: sprechen--- ‘to speak’ --- aussprechen --- to speak out, express Ausschwung --- ‘to swing’ --- ??? --- to fulfill the swing In German gymnastics ‘Anschwung’ refers to

a movement away from the resting point to a place of potential kinetic energy,

a preparation. ‘Ausschwung’ then is the release of the potential

energy into the main action. These are a bit awkward to describe in English,

but they might be translated as the preparation-swing and action-swing: preparation-swing (Anschwung; 29, 73, 77) action-swing (Ausschwung; pp. 29, 72-73, 77) Movement is also sometimes described as how the

body may be leading (Führung) the movement or into which

direction the movement is led: leading (Führung;

pp. 28, 44-45, 58, 62, 68, 89, 91-94, 103) (ie. guiding) [cf. ‘perform’] leading

with the body: right-leading (rechtsführend; pp. 29-32, 70, 76, 78, 95) left-leading (linksführend; pp. 29-32, 79) progressive-leading (Fortführung; p. 89) leading

in space: inwards-leading (Einwärtsführende; p. 78) led-forwards (vorgeführt; p.

58) direction

led very widely (Richtung sehr weit geführt; p. 103) direction

led narrowly (Richtung eng geführt; p. 103) led-through (weitergeführt; p. 103) Occasionally movement is described as the progress

(Fort) or progression (Fortschreitung): progress (Fort) progression (Fortschreitung;

pp. 62, 67, 100, 102) progressive-leading (Fortführung; p. 89) movement-progression (Fortbewegung; pp. 62, 65) movement-progression-elements (Fortbewegungselemente; p. 62) =

elemental attributes of movement “manner” (effort) or “form” (space) Several other concepts are also used less

frequentyl to describe movement: activate (Eingeschaltet;

p. 70) to turn on a potential energy action (Handlungen;

pp. 1-3) Commitment (Gegangen,

begehen, pp. 70, 80); to actually be going. development

(Ablaufes, pp. 64, 74, Verlauf, p. 89); ‘running through’ happening (Geschehen;

pp. 63, 78) event (Ereignisse;

pp. 2-3) phases (Phasen;

pp. 3, 77) sequencing (Satz;

pp.14, 100); a sentence, clause, or syntax process (Vorgang

, pp. 3, 55); ‘going forward’ proceeding with the action |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Effort (Eukinetics) and

Space (Choreutics) The modern-day concepts of ‘effort’ and ‘space’

are generally used to refer to two major categories of movement analysis: 1) Effort:

movement quality & dynamics 2) Space:

movement form & shape While Choreographie is primarily

concerned with spatial aspects of movement, the effort (dynamic) aspects are

also presented with an integration and interaction with space. Laban often organised effort and space with

identical models. The conception of the “dynamosphere” in Choreutics uses

polyhedral (spatial) models to represent relationships (aka. ‘directions’)

amongst effort dynamics (Laban, 1966, p. xxx; Salter 1967, 1977, 1980). These same parallel model for effort and space is

used throughout Choreographie: Spatial forms are considered to

be the “primary-direction” (Hauptrichtung)

or the “primary-stream” (Hauptströmung) while effort qualities

are considered to be the “secondary-direction” (Nebenrichtungen)

and the “secondary-stream” (Nebenströmungen). Laban used the same terminology later in his

English book Choreutics where he describes:

“... a kind of secondary

tendency appears in the body, namely a dynamic quality” ... [these] “dynamic

actions . . . create ‘secondary’ trace-forms” ... [so called since the] ...

“dynamospheric currents are secondary in respect of their spatial visibility”

(Laban, 1966, pp. 31-33, 36). In differentiating between effort and space, it appears

that Laban encountered an inevitable conflict between analysis and synthesis.

On the one hand there is a need to distinguish between effort and spatial

aspects for the sake of notation and analysis, while on the other hand in the

phenomenon of actual movement these are thoroughly integrated and inseparable: “Third fact of

space-movement Although

dynamospheric currents are secondary in respect of their spatial visibility,

. . . in reality they are entirely inseparable from each other. It is only

the amazing number of possible combinations which, in order to comprehend

them, makes it necessary for us to look at them from two distinct angles,

namely that of form and that of dynamic stress.” (Laban 1966, p. 36) In some places the effort / space distinction is

considered as two types of structures: 1) expressive-structure

(Ausdrucksgebildes; pp. 62, 83) 2) form-structure (Formgebilde;

p. 89) Effort and space are also distinguished as movement-progression-elements

(Fortbewegungselemente; p. 62), subdivided into two major headings: 1) “movement-manner” (Bewegungsart;

p. 62) dynamic quality of movement Similarly they are also distinguished as two

basic “movement-concepts” (Bewegungsbegriffe; p. 80) or “movement-contents”

(Bewegungsinhalte; title chapter 27, p. 80) namely: 1) “expressive-contents” (Ausdrucksinhalte;

p. 80) qualitative dynamics attributes. 2) “movement-forms” (Bewegungsform;

pp. 62, 80) spatial shape and orientation. However, most often the distinction is between

either “primary” (space) or “secondary” (effort): Primary- (haupt-)

(ie. the spatial form, rather than the dynamic form) primary-direction (Hauptrichtung; pp. 29, 39, 49, 51-53, 74, 78, 86) primary-dimensional (Haupt-dimensionalen; p. 79) primary-inclination (Hauptneigungen; pp. 29, 37, 40, 78) primary-movement-line (Hauptbewegunglinie; p. 63) primary-stream (Hauptströmung; pp. 74, 76-77) primary-swing (Hauptscuwunge; pp. 28, 36, 40, 101) primary-tension (Hauptspannung; p. 3) primary-focus (Hauptaugenmerk; p. 62) primary-figure (Hauptfigur; pp. 59-61) primary-essence (Hauptsachlichen; pp. 55, 63, 82, 87) Secondary- (Neben-)

[cf. ‘primary’] (ie. ‘Effort’ rather

than ‘Space’) secondary-direction (Nebenrichtungen; p. 75) secondary-line (Nebenlinie; pp. 62-63) secondary-striving (Nebenstrebungen; p. 70) secondary-arm-movement (Armnebenbewegung; p. 87) secondary-streams (Nebenströmungen; title chapter 25, pp. 63, 74-76, 79, 102) secondary-sign (Nebenzeichen; p. 102) secondary-stream-sign (Nebenströmungszeichen; p. 102) Together with these parallel concepts of

“primary-directions” (spatial forms) and “secondary directions” (effort

qualities) came other models for close interactions between spatial forms and

effort qualities: ·

The theory of effort / space affinities

proposed that certain effort qualities have a tendency to occur with certain

spatial directions (see “effort-space affinities” below). ·

Notation signs: in some cases the same (or

very similar) set of notation signs would be used for both spatial forms and

effort qualities. For example Laban

used ‘vector signs’ for both spatial directions and also sometimes used the

same signs for effort qualities (1926, p. 79). And this same practice continued in Choreutics

(1966) where Labanotation direction signs, together with a letter “s” were

used to represent effort qualities. ·

Organizational models: Sometimes both

areas (the spatial concepts and also effort concepts) were organised

according to the same polyhedral models, for example referred to as the

“kinesphere” and the “dynamosphere” (Laban 1966). ·

Transformations: All of these

parallel associations between concepts of spatial forms and concepts of

effort qualities supported a practice of transforming a spatial form into an

effort form, and vice versa (see “transformations” below) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Effort, Dynamic qualities While Choreographie

focus primarily on the spatial structure of body movements, the forerunners

of the four effort factors presented in later works (Laban & Lawrence

1947) are already well developed here. In Choreographie

the dynamic qualities are generally referred to as the: intensity (Intensität;

pp. 76-77): intensity-manifestations (Intensitätserscheinungen; p. 78) or ‘intensity-shining’ intensity-degrees (Intensitätgrade; p. 77) intensity-scale (Intensitatsskala; p. 74); a range between two effort polarities regulators-of-intensity (Intensitätsregulatoren; p. 74) intensity-nuances (Intensitätsnuancen; p. 76) spatial-temporal-dynamic

nuance (räumlich-zeitlich-dynamische

Nuance; pp. 74, 75) form-nuances (Formnuancen; p. 80) [ie. an ‘effort-form’] movement-nuances (Bewegungsnuancen; p. 80) The four effort factors of space, weight, time,

and flow, are described with a variety of concepts: Weight Effort factor: dynamic

nuance (dynamische Nuance; pp. 74-75) force

(Kraft; pp. 4, 74, 76, 78) taking-of-force (Kraftholen; pp. 74-75), Weight Effort elements (fighting / indulging continuum) degree-of-tension (Spannungsgrad; p. 4) strong (stark; pp. 74-78) to weak (schwach; pp.

74-78) tensile-force (Spannkraft; p. 78) non-tension

(Abspannung; pp. 74-75) strongly

tensioned (stark gespannte;

p. 75) relaxing (Erschlaffen, 75) Time Effort factor: temporal

nuance (zeitlich Nuance; pp. 74-75) time (Zeit; pp 74-79) speed [‘speedyness’] (Geschwindigkeit; pp. 76, 78) timing-influences (Zeitbeeinflussungen; p. 75) Time Effort elements (fighting / indulging continuum) degree-of-speed (Geschwindigkeitsgrad; p. 4) quick (rasch; pp. 74-76, 78-79) vs. slow (langsam; pp. 74-79) speedy (geschwind; p. 74) fast (schnell; p. 77) accelerate (beschleunigt; p. 78) Space Effort factor: spatial

nuance (räumlich Nuance; p. 75) spatial-metric

nuance (raum-metrische Nuance; p 74) spatial-extent (Raumweite; p. 76) spatial-metric (Raummetrik; p. 63) spatial-measurement (räumlich-metrische; p. 63) Space Effort elements (fighting / indulging continuum) degree-of-size (Weitegrad; p. 4) near (nah; p. 74) to far (weit; pp. 74-77) narrow (eng; pp. 19, 75-78) wide; width

(weit; Weite; pp. 19, 78-79) furthest-reaching

(weitgehendste; p. 75) Flow Effort factor: flux

(Flucht; pp. 4, 74, 76, 78 [to flee, to escape]), flux-intensity (Fluchtitensitat; p. 75), movement-flow (Bewegungsflusses; p. 102) flying, fleeing, fleeting (fliegend, fliehend, fluchtend;

p. 75) lability-fluctuations (Labilitätsschwankungen; p. 74) Flow Effort elements (fighting / indulging continuum) degree-of-lability (Labilitätsgrad; pp. 4, 74) stability (Stabilität; pp. 63-64, 75-78) to lability

(Labilität; pp. 63-64, 75, 77-78) rigid (starr; pp. 74-75, 77) vs. mobile

(bewegt; p. 74) stiffening (erstarrend; p. 78) fleeting

(flüchtig; pp. 18, 77) (ie. volatile) flow (Fluß; pp. 75, 102) flows (abfließt; p. 22) flowing (fließend; pp. 74, 76, 103) flinging (schleudernd; p. 74) Discussion of Effort Factors: Flow Effort. In the English book Effort (Laban &

Lawrence, 1947, pp. 7 - 17) a distinction amongst the four effort factors is

made by identifying flow effort as the aspect of “control”, while weight,

space, & time efforts are considered to be “exertions”. This

‘three-plus-one’ structure of effort leads to the designation of the eight

effort ‘actions’ (float, punch, glide, slash, dab, wring, flick, press -- all

the combinations of Weight, Space, and Time) as distinct from the aspect of

control (flow). Similarly in Choreographie flow effort is treated differently,

considered as the “flux-intensity”

(Fluchtitensitat) while space, time, and weight efforts are considered

to be the “intensity-nuances” (Intensitätsnuancen) described

collectively as the “spatial-temporal-dynamic

nuance” (räumlich-zeitlich-dynamische Nuance). The system of effort / space affinities (see

below) also reveals the special role of flow effort. In Choreographie

and also later English writings, weight, space, and time efforts are each

affined to one of the three dimensions; vertical, lateral, and sagittal; whereas

flow effort is the odd-one out - without

any dimension for an affinity. Instead, the more fundamental role of flow is

made explicit in Choreographie (pp. 75-77) by identifying it as the “degree-of-lability”; ranging from “stability” affined with dimensional

orientations and “lability”

affined with diagonals. Weight Effort. Weight

effort in Choreographie is referred to as “force” (kraft)

which is a very active concept, expressed as the “taking-of-force”(Kraftholen). This same concept of force was reiterated

when Laban wrote his first English book Choreutics

(Laban, 1966, p. 55 [written in 1939] ), and only later developed to strong

or light “weight” (Laban & Lawrence, 1947, p. 13). The concept of the

body’s “weight” (Gewichts) also does appear in Choreographie

but primarily in regards to the

balancing of equal-weight in “equilibrium” (Gleichgewicht). In Choreographie weight effort is

also closely associated with “tension” (spannung), not as the

modern-day concept of ‘spatial-tension’ but as forceful muscular tension. The

quality is explicitly labeled as the “degree-of-tension” (Spannungsgrad)

or as the “tensile-force” (Spannkraft) ranging from “relaxing,

non-tension” (Erschlaffen, Abspannung) to “strongly

tensioned” (stark gespannte). These

earlier concepts weight effort as force

and tension might be similar to

the idea of “increasing and decreasing pressure” as sometimes used to

describe weight effort. This has a

more active feeling about using one’s weight with active exertions and

gradations in pressure (Lamb 1965; Lamb & Turner 1969; Lamb & Watson

1979; Moore 1982). Space Effort. In Choreographie space effort is

considered mainly in terms of size; as the “spatial-extent” (Raumweite) or “degree-of-size” (Weitegrad) ranging from “near” (nah) and “narrow” (eng) to “far” or “wide” (weit; Weite). These spatial concepts include

the body shape, whether narrowing with smaller trace-forms or widening with

larger spatial forms and is similar to the modern-day concept of ‘size of

kinesphere’. This consideration of ‘size’ seems to change in Laban’s

English works where the shape of the pathway became more important with space

effort described as “directional flux” ranging from “straight” to “roundabout”

(Laban 1966 [1939], p. 55) or as the “shape of its path through space” ranging

from “flexible” to “direct” (Laban 1963, p. 54). Space effort has evolved to present-day concepts

in Laban Movement Analysis as a quality of ‘focus’ from direct and

pin-pointed to flexible and meandering.

However these concepts still associate back to the original concepts

of space as external spatial form and design and (this author’s personal

opinion) observations and awareness of space effort (quality of focus -

direct to flexible) cannot be completely be divorced from choreutics - space

harmony (form of movement - straight to curving). Time Effort. Modern-day concepts of time effort seem to have

remained more or less consistent with those in Choreographie. The only issue, and this difference is

still present amongst different practitioners in different areas of the world

today (this author’s observation), is whether time effort is conceived as “speed” (Geschwindigkeit)

ranging from “fast” (schnell) to “slow” (langsam) or whether

time effort is conceived as active changes in speed, thus either to “accelerate”

(beschleunigt) or decelerate. The first concept of fast / slow can indicate steady, unchanging velocities, while the

second concept of accelerate /

decelerate specifies how the timing has active moment-to-moment changes

in speed. In his later English writings

Laban used concepts of “quick” or “sudden” and “sustainment” which

distinguish time effort from simply ‘fast’ or “slow” tempos (Laban 1963,

1966; Laban & Lawrence 1947). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Creating Space A major focus of Choreographie is

devoted to analyzing the “space” (Raum; pp. 74, 76) of body

movements, which is used in over 20 compound terms (see Translation Index).

The intention, necessary to create a movement-notation system, is to identify

the spatial-organisation (Raumordnung; title chapter 7, p. 19)

of body movement. A variety of basic concepts of space are derived

from the German root verb ‘bilden’ (to shape, to mold, to form, to

create) and its associated noun ‘Bild’

(drawing, painting, photo, picture) or ‘Gebilde’ (structure, project,

construction, creation, shape). These concepts in Choreographie relay the idea of space being ‘created’ and

these were carried over into Laban’s Choreutics (1966) where spatial forms

only exist when there are continuously created by body movement. Likewise, Laban’s later English concept of

a “trace-form” also appears to be

derived from the German ‘Formbild’,

one of the many compound words with this same German root: structure (Gebilde) [could also be: project, construction, creation,

shape] to

create (bilden) [could also be: to shape, to

mold, to form] picture (Bild) [could also be: drawing, painting, photo] to

create bilden / bildet (pp. 3. 5, 36,

49-50, 71, 88) structure Gebilde, gebildet (pp. 4, 28, 46, 62, 83, 85, 88) complete-structure Gesamtgebilde (p. 34) expressive-structure Ausdrucksgebildes (pp. 62, 83) form-structure Formgebilde (p. 89) picture Bild (p. 35) mirror-image Spiegelbildlich (pp. 3, 25) spiegelbild (p. 34) portrait Abbilder (p. 84) portrayal abbild (p. 40) prototypes Vorbilder (p. 4) [literally, created-before] form-picture Formbild (p. 4) (eg. trace-form?) spatial-picture Raumbild (pp. 20-21, 64) written-picture Schriftbild (p. 101) movement-picture Bewegungsbilds (p. 100) image Ebenbild (pp. 40, 42) - eben;

even, the same trace-form (Formbild; p. 4) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Space - Kinesphere Spatial zones are distinguished in Choreographie. The “kinesphere“ coined by Laban as “the

sphere around the body whose periphery can be reached by easily extended

limbs” (1966, p. 10) appears to have developed from the German ‘Umraum’

(literally, the ‘surrounding-space’ or ‘the space around’). Other spatial zones are also referred to: dance-space (Tanz-raum;

pp. 62, 64) ; the overall space of the room or setting. dance-circle (Tanzumkreis;

p. 11) ); virtually synonymous with kinesphere, stressing the circle. kinesphere (Umraum;

pp. 17, 40, 89) bodily-kinesphere (Körperumraum; pp. 62, 64) movement-kinesphere (Bewegungsumraumes; p. 21) kinespheric-points (Umraumpunkte; p. 29) kinespheric-inclinations (Umraumneigungen; p. 40) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Form The kinesphere is created by varieties of form

(Formen) which appears in over 20 different German compound words (see

Translation Index). From the first sentence of Choreographie,

an “account of the world of dance-forms” is proposed (p. 1) and this is begun

with a fundamental distinction between: static form-theory (statische Formenlehre; pp. 3-4) [ie. study of

positions] analyzing

stationary conditions (Zustände; pp. 1-3, 17, 74-75 versus dynamic form-theory (dynamishe Formenlehre; pp. 3-4) [ie. study of motions] analyzing

progressive events (Ereignis; pp. 2-3) Several types of forms are discussed: spatial-forms (Raumformen; pp. 1, 2, 84, 88) dance-forms (Tanzformen; p. 1) trace-form (Formbild; p. 4) (or ‘form-picture’) [cf. form-structure] movement-form (Bewegungsform; pp. 62, 80) pathway-forms (Wegformen; pp. 10, 80, 99) step-forms (Schrittformen; p. 54) A variety of concepts are introduced to decipher

structural components of forms: basic-form (Grundform; pp. 4, 74) singly-formed (einförmig; p. 56) complete-form (Gesamtform; p. 64) form-combination (Formkombination; pp. 83, 89) form-series (Formreihung; p. 89) form-component (Formteiles; pp. 4-5, 45, 75) form-kernel (Formkern; p. 1) form-element (Formelementes; pp. 2, 3) form-structure (Formgebilde; p. 89) Symmetries and relationships amongst forms are

explored (more details below) kindred

forms (verwandte Formen; p. 1) form-changes (Formveränderungen; p. 83) form-transformations (Formwandlungen; pp. 1-2) [See ‘transform’] form-transformation-processes (Formwandlungsprozesse; p. 1). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Form Structures Laban’s concepts of “gathering” and “scattering”

from his later English works (Laban 1966, pp, 49, 175; 1980, p. 83) appear to

have already been present in Choreographie

as “Heranrufen” and “Wegstossen” (p. 82) (literally ‘calling-together’

and ‘pushing-away’) and distinguished as the two “simplest purposeful-movements”

(p. 82). Analyses of form-structure (Formgebilde;

p. 89) follows the Euclidean framework: point (Punkte;

pp. 11, 22, 29, 32-33, 45) having only location, a single spot in space orientation-points (Orientierungspunkte; p. 11) kinespheric-points (Umraumpunkte; p. 29) stopping-points (Haltepunkte; p. 28) end-point (Endpunkt; p. 33, 49) starting-point (Anfangspunkt; p. 49) floor-contact-point (Bodenberührungspunkt; p. 69) supporting-points (Stützpunkte; p. 68) line (Linie;

pp. 17, 22), having length through space spatial-line (Raumlinie; p. 50) movement-line (Bewegungslinie; pp. 49, 63, 102) swing-line (Schwunglinie; p. 71) secondary-line (Nebenlinie; pp. 62-63)

(ie. an Effort) direction-line (Richtungslinie; p. 99) side-line (Seitenlinie; p. 24) plane (Ebene;

pp. 49-50) only used twice apparently to describe the quality of flatness. plane (Fläche;

pp. 17, 22-23, 75) describing the shape of flatness dimensional-planes (Dimensionalflächen; pp. 23, 36) high-deep-plane (Hochtief-Fläche; p. 22) right-left-plane (Rechtslinks-Fläche; p. 22) fore-back-plane (Vorrück-Fläche; p. 22) plastic (plastische;

pp. 3-4, 64, 78) sculptural, moldable, clay-like trait filling a volume of

space. “Plastic”

(plastische) is distinguished from “three-dimensional” (Drei-Dimensionalität; p. 17) which

Laban uses in other places. Whereas ‘plastic’

describes form of volumetric

molding of the body, ‘three-dimensional’ describes orientation relative to vertical, lateral, & sagittal. Thus,

the form of a line or a plane can also have a three-dimensional orientation. Further categories of form-structures are based

on the “step-forms” (Schrittformen; p. 54), in Choreographie Laban gives

credit to Feuillet as the earlier source for these, while later in his

English book Choreutics, Laban (1966, p. 83) presents the same group

of forms but doesn’t mention Feuillet. These four forms (or more? see Chapter 17 for

discussion) are drawn upon for their spatial concepts as well as their

notation signs. In Choreographie it can be seen

how Laban draws on the French terminology (from Ballet and Feuillet) and then

also provides German terms for the same concepts (pp. 54-55, 80, 94): straight (droit) French

from Feuillet (gerade) German

open

(ouvert)

French from

Feuillet (offener; offen) German round (rond) French

from Feuillet (runder) German twisted (tortillé) French from Feuillet (gewundener) German (Further detailed discussion of these forms can

be found in Longstaff 1966, Section IVB.32 Path Hierarchy. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Pathways One way forms can be produced are by pathways

through space, occurring as paths of limb gestures also for larger floor

paths. The pathways might create any

of the form structures (outlined above).

Several concepts of pathways are used in Choreographie: pathway (Weg;

title chapter 21, pp. 8, 10, 60, 65, 68, 80, 84) (lit. ‘way’) spatial-pathways (Raumwege; p. 102), pathway-forms (Wegformen; p. 80) floor-pathway (Bodenweg; pp. 65-66) ground-plan-pathway (Grundrissweg; p. 65) pathway-segments (Wegabschnitte; p. 11) circuit-pathway (Kreisweg; p. 36) free

pathway (Freier Weg; p. 65) connecting-pathways (Verbindungswege; p. 22) pathway-signs (Wegzeichen; p. 102) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Orientation

A principal component of orientation is an

analysis of “direction” (Richtung)

and developing a “direction-theory” (Richtungslehre; title

chapter 4, p. 13) including: basic-directions (Grundrichtungen; pp. 26, 32, 74) direction-elements (Richtungselemente; p. 64) directional-value (Richtungswert; p. 13) primary-direction (Hauptrichtung; pp. 29, 39, 49, 51-53, 74, 78, 86) While the concept of a “secondary-direction”

(Nebenrichtungen) is used, in Choreographie

this refers to an effort quality. In

the topic of ‘spatial orientation’ the focus is on “spatial-directions”

(Raumrichtungen; pp. 18, 24, 65, 84) such as: spatial-direction-concepts (Raumrichtungsbegriffe;

p. 8) spatial-direction-chords (Raumrichtungsakkordik; p. 25) spatial-direction-combinations (Raumrichtungenkombinationen; p. 84) For example, these consist of: directional-aim (Zielrichtung;

p. 77) action-swing-direction (Ausschwungsrichtung; pp. 29, 72) direction-line (Richtungslinie; p. 99) position-directions (Positionsrichtungen; p. 13) falling-direction (Fallrichtung; p. 68) directional-placement (Richtungseinstellung; p. 1) striving-direction (Streberichtung; pp. 78, 86) direction-groups (Richtungsgruppen; title chapter 26, p. 78) directional-correlations (Richtungszusammenhänge;

p. 7) contrary-direction (Kontrarichtung; pp. 12, 20, 45, 86) counter-direction (Gegenrichtung; pp. 12, 36, 39, 95) And the aim is to develop “direction-signs” (Richtungszeichen; p. 103) to use in

notation. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Dimensions The first direction-elements (Richtungselemente)

are identified as the: dimensional (Dimensionale; pp. 8, 14, 17, 20-25, 28,

63, 78, ...etc. dimensional-character (Dimensionalcharakter; p. 78) primary-dimensional (Haupt-Dimensionalen; p. 79) high-deep-direction (Hochtiefrichtung; p. 80) forward-backward-direction (Vorruckrichtung; p. 80) right-left-direction (Rechtslinksrichtung; p. 80) Occasionally, as an alternative to right and left

“Side” (Seite; p. 25) is used, or: sideways (seitwärts, p. 59) sideways (seitlich; pp. 24, 26, 68, 75) (Lit. side-like, ie. across, lateral) side-impulse (Seitimpuls; p. 39) side-line (Seitenlinie; p. 24) body-side (Körperseite; pp. 64, 74) Or in some cases, instead of right and left “in and out” (ein und aus; p.

25) Inwards / outwards (einwarts, auswarts) inwards-leading

(Einwärtsführende; p. 78) outwards-swing (Auswartsschwung; p. 25) [cf. ‘sideways’] inwards-swing (Einwartsschwung; p. 25) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Dimensional Planes One of the fundamental spatial-laws is described

in Choreographie where each

dimension has a “double consequence” (zweifachen Auswirkung;

pp. 22-23) such that anatomical constraints induce the body to move in the

dimensions, not as lines, but in planes. The resultant Cartesian planes are

not square or round, but are elongated along the dimension out of which the

plane emerged. Accordingly, they are considered to be “dimensional-planes”

(Dimensionalflächen; pp. 23, 36), and each plane is named according to

which dimension is largest. This same description of the dimensions dividing

into planes, resulting in “dimensional planes” is reiterated in later English

writings (Ullmann 1955, pp. 29-31; 1966, pp. 139-141; 1971, pp. 18-21; for

review see Longstaff, 1996, IVA.82). These three cardinal planes are also considered

according to how they create a “separation” of the space (Scheide;

pp. 22, 27, 28) and referred to as: separation-direction (Scheiderichtung; pp. 36, 49) Thus, the conception of the three cardinal planes

begins with each dimension, which expands into a plane, which creates a

separation of the space: |

|||||||||||

|

Dimension |

Expands |

‘Dimensional plane’ |

Separation |

Anatomical term |

|||||||

|

high-deep (Vertical) |

right & left |

high-deep-plane (Hochtief-Fläche; p. 22) |

fore/back-separation (Vorruck-Scheide; pp. 22, 36) |

Frontal plane (or Vertical plane) |

|||||||

|

right-left (Lateral) |

fore & back |

right-left-plane (Rechtslinks-Fläche; p. 22) |

high/deep-separation (Hochtief-Scheide; pp. 22) |

Transverse plane (or Horizontal plane) |

|||||||

|

fore-back (Sagittal) |

high & deep |

fore-back-plane (Vorrück-Fläche; p. 22) |

right/left-separation (Rechtslinks-Scheide; pp. 22) |

Medial plane (or Sagittal plane) |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Diameters The concept of diameters or diametral

(French-based Diametrale; p. 86) appears only once in Choreographie,

and in this case refers generally to any diameter through the sphere of the

movement space. This is different than how Laban used the term in

Choreutics (1966 [1939], pp. 11-16) where the “diameter” was

specialized to refer only to ‘planar diagonals’ (passing across opposite

corners in one of the Cartesian planes).

This special definition of “diameter” appears to

have developed later, and its absence in Choreographie

is reiterated in the notation methods which have signs for dimensions and

diagonals and inclinations, but no signs for planar-diagonals (in Choreutics

called “diameters”). The absence of ‘diameters’ in Choreographie may be because

the conception of space and notation was fundamentally different at that

time. Here the basic concepts were the

dimensions and the diagonals and their interaction (deflections) which lead

to the 24 inclinations. The

inclinations are based in motion. Later, by the time Laban wrote Choreutics (1966

[1939]) the notation system had become based in points - positions, and thus

inclinations because more obscure in favor of the simpler position-based

‘diameters’. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Diagonals The “three-dimensional”

(Drei-Dimensionalität; p. 17) orientation of “Diagonal” directions are referred to in Choreographie

primarily with the German “Schräge” (pp. 8, 13-14, 19, 21, et.

seq.) but also occasionally the French-based “Diagonale” (pp. 6, 11,

19, 86, 119) is used. Both of these have been translated into diagonal

since this is the term used in Laban’s later English writings. However, in

one place both terms are used in the same sentence, and so in this single

case Schräge is translated as “oblique” (p. 6). It is not clear what distinction could be implied

between the German and the French concepts but it may be that Laban was

developing a characteristically ‘German’ style and so preferred to use Schräge

rather than Diagonale with its associations to ballet. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Spatial Deflections &

Inclinations Of all his published works, Choreographie may contain the clearest presentation of

Laban’s unique idea of a “deflected

dimensional-system” (abgelenkte Dimensionalsysteme; p. 36). This is explicitly laid out (pp. 13-14),

beginning with a “pure diagonal” (reine Schräge; p. 14)

which has a slope with equal components of all three dimensions. The slope refers to a “numerical measure of the

inclination or steepness of the line” (Munem & Foulis 1986, p. 137) and

is typically represented as: slope

= {rise / run} rise = distance changed along the vertical run

= distance changed along the

horizontal For a three-dimensional slope, an additional run

can be added, thus: slope

= {vertical rise / lateral run / sagittal run} Thus, for a “pure diagonal” the three-dimensional

slope would be: slope = {1 / 1 / 1} Laban then conceives that pure diagonals will “deflect”

(ablenken; pp. 11, 13, 17-19, . . . etc.). This German term could also be translated

as: to turn aside, to refract, to distract, to diffract, to parry, to avert,

or to divert; and seems to indicate an energetic process, perhaps associated

with Laban’s use of saber fencing as a model for spatial sequences. The translation “deflect” is maintained

here since this is used extensively in Laban’s English writings. Several other concepts similar to deflection are used

less frequently: Movements must yield (ausweichen;

pp. 9, 18-19) around the body and so become deflected; Forms will deviate

(beugen; pp. 10-11, 92) according to the physicality of the body; Directions might diverge (Abweichende;

pp. 9, 11, 22, 65), away or towards another direction; Or directions might burgeon (Ausschlag;

p. 22) a German term also translatable as deflect; knock out; shake out; beat

out; bud out; lash out; to swing, which describes an active, forceful,

dynamic quality to a deflection. The result of deflections is that regular

orientations (eg. pure dimensions or pure diagonals) slightly re-orient into

irregular 3D slopes referred to as “inclinations (Neigungen;

pp. 13, 29-31, . . . etc.). Laban

explains that an inclination might be conceived as a dimensionally deflected

diagonal, or a diagonally deflected dimension, and that these two options are

essentially equivalent: “There appear

two possibilities: To put forward either a diagonal deflected through a

close-by dimensional, or alternatively, a dimensional deflected through one

of the closest diagonals. Since to us the dimensional-concepts are more

familiar, we shall relate the positional-inclinations to these.” (Laban, 1926,

p. 13) The resultant 24 inclinations are considered to

be the “basic-directions” (Grundrichtungen; pp. 26, 32, 74) and

are referred to according to their dimensional content as either: |

|||||||||||

|

inclination |

dimensional deflection |

|

3D slope {vertical / lateral / sagittal} . |

||||||||

|

flat |

(flachen) |

right-left |

(lateral) |

of any diagonal |

prototype 3D slope |

= {1.6 / 2.6 / 1 } |

|||||

|

steep |

(steile) |

high-deep |

(vertical) |

“

“ “ |

“

“ “ |

= {2.6 / 1 /

1.6} |

|||||

|

suspended |

(schwebend) |

fore-back |

(sagittal) |

“

“ “ |

“

“ “ |

= {1 / 1.6

/ 2.6} |

|||||

|

The irregular 3D slopes

of the inclinations becomes an important aspect when examining the the order

of movements in Laban’s system of “scales”.

The uneven components in the 3D slope have been variously referred to

as the “uneven stress on three spatial tensions” (Dell,

1972, p. 10), as “three unequal spatial pulls” or “primary, secondary, [and] tertiary spatial

tendencies” (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, pp. 38, 92-93) and in Choreographie as “extremely” ,

“somewhat”, or “scarcely” “outspoken” (Laban, 1926, pp. 25-26). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Effort / Space Affinities

The idea of affinities

is described as a “preference” (Bevorzugung; p. 78) or how certain

directions and intensities (efforts) will be “preferably” (vorzugsweise;

pp. 78, 80) performed together or how they will have an “alliance” (verbunden;

pp. 15, 75, 80). Interestingly, when presenting the affinities for

the Right A-scale (p. 79), the results are NOT as simple as following the

basic scheme of affinities. Instead

only every other inclination is given the same effort affinity as its

greatest dimensional component: |

|||||||||||

|

Effort - Space Affinities with the Right A-scale (vector signs refer to effort qualities) (Laban 1926, p. 79 [Labanotation direction signs

and “flat”, “steep”, “suspended” added -- JSL] ) |

|||||||||||

|

This list of effort / space affinities for the

A-scale are not typical for modern-day concepts in Laban Movement

Analysis. The greatest dimensional

component of each inclination (flat, steep, suspended) is not paired with its

corresponding effort affinity (space effort, weight effort, time effort,

respectively). However, if the A-scale is considered to be a

deflection of the dimensional scale (see Chapter 8, p. 25; Chapter 8 note #8;

also described by Laban 1966, pp. 42, 80), then the affinities here DO follow

the correct pattern of efforts in the order of the dimensional scale

(otherwise known as the “defense scale”). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Transformations An inseparable part of Laban’s “dynamic

form-theory” (dynamishe Formenlehre; pp. 3-4) is an analysis of

the continual changes, mutations, transformations (and their structural

similarities) amongst spatial forms. These processes are generally described

regarding how a spatial or dynamic form might “transform “ (wandelt;

p. 77) and other variations on this same German root are also used: transformation (Wandlung;

pp. 1) form-transformations (Formwandlungen; pp. 1-2) form-transformation-processes (Formwandlungsprozesse; p. 1) transformable (umwandlungsfähig;

p. 99) condition-transformations (Zustandswandlungen; p. 1) Several other transformational concepts can be

translated with the English prefix “trans-”

(from the German über-, lit. ‘over’), the most common of these being “transfer”

(Übertragen; pp. 9, 12, 57-58, 87, 92, 97, 99 [could also be

‘translate’ or ‘transmit’]), used to

refer to the action of transferring the body weight to a new location in the

room. Other ‘trans-’ concepts are

used more rarely: transfer (übertragen;

p. 28) [translation of a spatial form from peripheral to central moves] transmit (überliefert;

p. 8) [‘transmitted through history’] transport (überführt;

p. 77) [literally, leading-over] transport-towards (hinüberführen; p.

28) transmute (umgeformt;

p. 3) transpose (verlegt;

p. 19) [could be: transfer, to lay, to move, to shift] transpose (hinübergeleitet;

p. 1) [literally: to escort or accompany over] moved-across (hinüberbewegt; p. 60) Other transformational concepts are also used,

including: exchange (Wechsel;

pp. 33, 68, 75-76, 92) exchange of directions (between A- & B-scales) or

exchanges from one dynamic quality to another. displaced (verlagern;

p. 86) - translation symmetry between counter-directions in a 4–ring; manifold (mannigfaltigster;

p. 86) - variety of bodily coordinations with the same trace-form. modify (abwandeln;

p. 1) [same root as Wandlung] variation (Variation;

pp. 18, 55, 87) varieties (abarten;

pp. 55, 76) Elaboration-possibilities (Ausbaumöglichkeiten; p. 19) One unique type of transformation indicated in Choreographie is associated

with effort / space affinities and

involves changing a spatial form into an effort quality and vice versa. This is illustrated in plate 19 where one

person completes a “purely formal”

(rein formal) spatial direction while the other completes an

associated “expressive tension” (Ausdrucksspannung). This is presented in more detail in Choreutics

where Laban describes how one can “transform” a dynamic sequence (effort

qualities) by “enlarging and transferring” it to create a spatial sequence

(1966, p. 60). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Symmetry Transformations often result in various forms of

“Symmetry” (Symmetrie) which is used to describe opposing

spatial directions (p. 86), as well as being named as the simplest form of

‘harmony’:

“Dance is movement, its

tendency is labile. Nevertheless the harmonization of movement is allied with

a certain stabilization. The simplest form of harmony is symmetry,

equilibrium.” (Laban 1926 p. 15) This description gives an indication of the

association between body organisation and spatial symmetry, and how this

association is at the heart of Laban’s concepts of ‘harmony’. In Choreutics a similar statement goes

into more detail:

“A most important way of

attaining what we call equilibrium is found in the so–called movements of

opposition. When one side of the body tends to go into one direction, the

other side will almost automatically tend towards the contrary direction. We

feel the loss of equilibrium and produce, often involuntarily, motions to

re-establish balance. . . . This points out the association between body

reflex coordination (countermovements to maintain equilibrium) and spatial

symmetry (limbs extending into opposite directions), thus “equilibrium

through symmetric movements”. This idea is taken one step further in the “law

of countermovement” stated in Choreographie where Laban asserts that the

movement to maintain equilibrium is not exactly in the opposite direction,

but only “moving towards a nearly

opposite spatial-direction” (p. 18).

Again, when describing the “preparation-swing” occurring just before

each “primary direction” in a movement sequence, that “in fact this

preparation-swing lies in a completely particular specific direction and not exactly opposite the primary

direction” (p. 29 [italics mine]). Thus it is not purely symmetrical movements in

countermovements for maintaining equilibrium, but instead it becomes a

sequence of “asymmetric movements which must necessarily be completed by

other asymmetric tensions or moves” (Laban, 1966, p. 90). These descriptions

are identical to an action-reaction reflex pattern of “dynamic equilibrium”,

as well-known in kinesiology studies: “After an

unbalancing movement is perceived, some motion is initiated to counterbalance

it and move the centre of gravity of the body back over the supporting base.

Typically, this countermovement is too great, producing an unbalancing

movement in the opposite direction. This calls again for detection and

countermovement. As the process is repeated, oscillation occurs.” (Rasch and Burke,

1978, p. 102) This idea of series of asymmetrical movements

while maintaining equilibrium becomes the source for deriving many of the

choreutic “scales”. In Choreographie

the concept of “Symmetry” is

sometimes specific to body parts and body structure: symmetrical-halves [of the body] (Symmetriehalften; p._) body-symmetry (Körpersymmetrie; p. 22) symmetry-divisions (Symmetrieteilung; p. 27) symmetrical divisions (symmetrischen Tielung; p. 33) symmetry-middle (Symmetrie-mitte; p. 27) Several specific aspects of symmetry are also

identified: proportion (Verhaltnis; pp. 7, 27, 36, 76, 84) parallel (parallel; p. 36), eg. between opposite edges of 4-rings parallelism (Parallelismus; p. 40) symmetry group, trioism (Trialismus; p. 40) three lines in a triangle (3-ring) mirror-image (Spiegelbildlich; pp. 2, 25, 34) inversion (Umkehrungen; p. 28) - a 3-D reflection; projection (Projektion; pp. 13, 65, 102) - duplicating a form with new

location and/or size; reversed (Gedreht; p. 101) - executing a form in retrograde; |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Relation, Correlation,

Correspondence Or generally described as a “relationship”

(Beziehung; pp. 8, 13, 28) harmonious-relationships (Harmonicbeziehungen; p. 88); counter-direction-relationships (Gegenrichtungbeziehungen; p. 62). When groups of spatial forms have symmetrical

relationships amongst themselves, they are sometimes described as being “kindred” or having a “kinship” (verwandt, Verwandtshaften;

pp. 1, 36-39, 78, 99). The German Verwandt is related to Wandlung (transformation / change) and

expresses how spatial forms might be different transformations of each other,

yet retain the same essence; for example, amongst groups of 4–rings (pp.

36-39), or between inclinations and their dimensional components (p. 78). Other concepts identifying relationships are: “Correlation” (Zusammenhänge;

pp. 68, 86), literally hanging-together, could translate as association,

coherence, connection, or relationship. This is a double-relationship, a

mutual hanging together, interrelation. This concept is used for spatial aspects: Spatial

Correlations (Räumliche Zusammenhänge; title

Chapter 28); directional-correlations (Richtungzusammenhänge; p. 7) Law

of Correlations (Gesetz der Zusammenhänge; p. 5) And it is also used for dynamics in effort: power-correlations (Gewaltenzusammenhängen; p. 81) Further, it is also applied to coordination

amongst body parts (see “body” above): limb-correlations (Gliederzusammenhängen pp. 86-87) (ie coordination across limbs) “Corresponding (Entsprechender; pp.

7, 9-10, 13, et. seq.); used frequently to indicate two features (lines, body-parts)

which are in agreement, accord, eg. arm motion towards the ‘corresponding’

counter-direction of a previous movement. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Opposition, Countermovement,

Equilibrium Various manifestations of oppositions and

countermovements are considered. The translation “opposition” is used for each of the three instances of the French

“Opposition” (pp. 7, 11, 98). In each of these cases it is explicitly

identified as being equivalent to the German “countermovement” (Gegenbewegung). An abundance of oppositional concepts are used,

primarily derived from the German roots: Gegen- (opposing, against, counter-, contrast) and Kontra- (contra-). The exact

difference between “Gegen” and “Kontra” is not explicitly clear. For example “Gegenrichtung” and “Kontrarichtung” could be translated

into identical English words. However

for the sake of maintaining the difference given in German, it is attempted

to consistently translate them into separate English terms: Gegen (opposing) opposing (Gegen) opponent (Gegner; p. 24) opposite (gegenüber; pp. 29, 34, 36, 59, 83, 86-87) opposition-placements (Gegenüberstellungen; p. 86) lying-opposite (gegenüberliegenden; p. 36) Gegen (against) against (gegen; p. 84) against-one-another (gegeneinander; pp. 25, 86) Gegen- (counter-) counter-leg (Gegenbeins; p. 20) counter-direction (Gegenrichtung; pp. 11-12, 36, 39, 95) counter-direction-relationships (Gegenrichtungsbeziehungen; p. 62) countermovement (Gegenbewegung; pp. 6-7, 11, 59, 84, 86-87, 98) countermovement-direction

(Gegenbewegungrichtung; p. 87) counterparts (Gegenteile; p. 78) counter-side (Gegenseite; pp. 75, 86-87) counter-swing (Gegenschwung; p. 11) counterweight (Gegengewicht; p. 18) [cf. equilibrium] Gegen- (contrast) contrast (Gegensätze / gegensätzliche; pp. 25, 74, 81, 86) contrast (dagegen; p. 39) contrast (Gegenteile; pp. 81, 86) contrasting (entgegengesetzte; pp. 18, 60) contradict (entgegensetzen; p. 74) Kontra- (contra-) contra-direction (Kontrarichtung; pp. 12, 20, 45, 86) contra-position (Kontraposition; pp. 10, 19, 27-28, 35) contra-position-inclinations (Kontrapositionsneigungen; p. 68) contrapunctual-situation (kontrapunktieren; p. 86) contrary (kontra; p. 45) Kontra- (counter-) counterpoint

(Kontrapunkt / kontrapunktieren; p. 86) Countermovements often arise as a reflex body

coordination for maintaining “equilibrium” (Gleichgewicht; literally, ‘equal-weight’, could also be

translated as ‘balance’). Together

with countermovements these play important roles in harmonic laws and in

construction of choreutic scales: equilibrium (Gleichgewicht;

pp. 5, 7-8, 75, 77, 81, 84-85) [literally ‘equal-weight’; ie. balance] law–of–equilibrium (Gleichgewichtgesetz; p. 18) equilibrium-condition (Gleichgewichtzustand; p. 75) equilibrium-strivings (Gleichgewichtstreben; p. 5) equilibrium-suspension (Gleichgewichtsschwebe; p. 86) equilibrium-tensions (Gleichgewichtsspannungen; pp. 3-4) equilibrium-moments (Gleichgewichtsmomente;

p. 77) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Tension In his English works Laban used the concept of “tension” and this also runs

throughout Choreographie (Spannung;

pp. 3, 11, 39, 63, 74, 93, 101) appearing in over 17 compound words. The use of Spannung seems to be

applied in three areas, which may however all be tied together. As a spatial stretch, reach or ‘span’

across a distance (eg. ‘wing span’).

As a reference to weight effort, force and tension in the muscles; and

perhaps similar to this, as tension in the body. Spatial Tension: In the

context of choreutics, ‘tension’ is often considered as spatial: spatial-tension-wishes (Raumspannungswünschen; p. 78) primary-tensions (Hauptspannung; p. 3) auxiliary-tensions (Hilfsspannungen; p. 3) individual-tension (Einzelspannung; p. 100) equilibrium-tensions (Glechgewichtsspannungen; p. 4) (stable plastic chords) four-five-tensioning (Vier-Fünf-Gespanntheit; p. 73) four-tensioned-star (Viergespannten stern; p. 88 Dynamic Tension: In the context of effort, ‘tension’ has

been considered as “tension flow”, the rhythmic alternation between releasing

and binding of muscular tension, which is a basis of effort flow (Kestenburg

(1967, pp 45-49; Sossin & Kestenberg Amighi 1999, p. 12). In Choreographie

it is used more specifically for the force of weight effort: force, degree-of-tension

(Kraft, Spannungsgrad; p. 4), tensile–force (Spannkraft; p. 78) non-tension,

weakness (Abspannng, Schwache; p. 74) relaxing, non-tension (Erschlaffen, Abspannung; 75). attentive-tension (Aufmerksamkeitsspannung; p. 80) strongly

tensioned (stark gespannte; p. 75) Body Tensions: Tensions are also considered in the body: body-tension (Körperspannung;

p. 93, 101) arm-tension (Armspannungen; p. 10) foot-tension (Fusspannungen; p. 93) hand-tension (Handspannung; pp. 93, 101) muscle-tension (Muskelspannung; p. 76) Several other ‘stretching’ concepts related to

bodily tension and Spannung are used, including extend (Tendiert;

p. 27), expand (Dehnen; p. 85), reach (Reichen

pp. 59, 74), and frequently stretch (Strecken, gestreckt,

vorstrecken, streckungen; pp 22-23, 28, 57-58, 74, 85, 93). |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Harmony The study of “harmonic” (harmonisch)

aspects of movement is one of the overlying themes of Choreographie

and Laban (1966, p. viii) defined “Choreutics” as “the practical study of the

various forms of (more or less) harmonized movement”. Concepts of harmony

are closely associated with symmetry (Symmetrie; p. 86), dance-logic

(Tanzlogisch; p. 89), and also to bodily reflex patterns of countermovement (Gegenbewegung) and equilibrium

(Gleichgewicht). Harmony is used within several other concepts: harmony, -ic, -ised (harmonisch; title chapter 10, pp. 7, 11, 29-30, 63, 68, 76,

86-87, 98, 101) disharmonic (disharmonish; p. 73) harmony-theory (Harmonielehre. p. 93) harmonic countermovement (Harmonische Gegenbewegung; p. 98) harmonic scales (harmonischen Skalen. p. 101) harmonious liveliness (harmonsche Lebendigkeit. p. 76) movement-harmonies (Bewegungsharmonien. p. 18) harmonious-relationships (Harmoniebeziegungen; p. 88) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Harmonic Laws The “choreutic laws” (Laban 1966, p. 26) or the

“binding laws of harmony” (Ullmann 1971, p. 1) are mentioned in the

literature, but of all Laban’s published writings, and perhaps of all past

and modern published works on Choreutics, also known as “space Harmony” (Dell

1972), the clearest, most direct and explicit statements of the proposed

“laws” of movement harmony may be found in Choreographie. The “laws” (Gesetz; ie. ‘rule’,

‘statute’) generally are referred to as: lawfully (Gesetzmassig; p. 101) basic-laws (Grundgesetze; p. 18) spatial-law (Raumgesetzlich; p. 18) regular-lawfulness (Gesetzmassigkeit; p. 14, 86, 101) harmonic

regular-lawfulness (harmonisch Gesetzmassigkeit; p. 86) lawfully-opposite (Engegengesetzte; p. 18) More specifically, several explicit laws are set

forward: law

of countermovement (Gesetz der Gegenbewegung; pp. 18, 25) law-of-equilibrium (Gleichgewichtsgesetz; p. 18) law-of-sequence (Gesetz der Folge; pp. 18, 25) [law

of] flowing-from-the-centre (Aus-der-mitte-fliessens;

pp. 18, 25) law

of spatial-direction-chords (Gesetz der

Raumrichtungsakkordik; p. 25) law

of correlations (Gesetz der Zusammenhange; p. 5) Descriptions of these laws can be found in the

text and also as found in the discussion of “dynamic equilibrium” (see above). Broader accounts of each laws and

integration into a system of laws of body movement can be a topic for future

practitioners and writers. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Theory, Teachings, Doctrines Several ‘doctrines’, ‘teachings’, or types of “theory”

(Lehre; p. 73) are established. These are not ‘theories’ in the sense

of a theoretical hypotheses, but are areas of ‘theory’ in the sense of larger

areas of study with teachings, doctrines and established principles of

knowledge derived from practical studies. In Choreographie