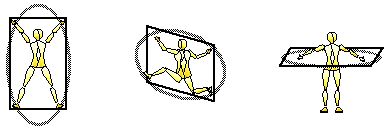

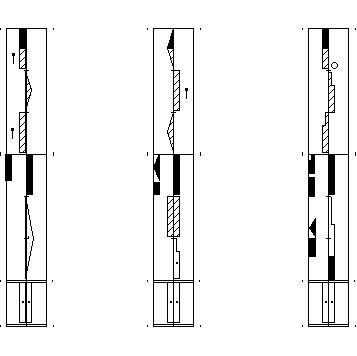

Figure 1. Three planes of movement described as door, wheel, and table planes.

____________

Introduction

This research began with a project to translate the early German text Choreographie (1926) [1] by Rudolf Laban (1879-1958), a dancer and theoretician, born in Hungary, growing up in Bratislava Slovakia, and later developing his work and schools throughout Europe, Great Britain, and United States [2]. The book explores several methods for notating human movement with various signs and abbreviations, these based on theoretical analyses of human movement potentials. [3] An entire chapter of the book is titled “Minuet” and consists of a verbal description of minuet dance steps, simple musical motifs, a Feuillet notation of a Z-figure, and account of a minuet sequence of 144 bars. However this chapter is completely disconnected from the rest of the text; nowhere in the chapter is mentioned any of the concepts discussed in the book, and nowhere in the rest of the book is made any mention of the minuet. The question arises as to why Laban considered the minuet important enough to devote an entire chapter to it and how this was significant for the development of his movement theories.

Rudolf Laban’s use of the minuet

This question was approached through interviews with students of Rudolf Laban who have personal experience with his practices, as well as reviews of Labanotations of the minuet to consider its movement forms and patterns. [4] The first revelation came from an interview with Roderyk Lange [5] where he pointed out how Laban’s description virtually copies a previous text and musical motifs of the minuet in the dance manual by Bernhard Klemm. [6] In a closer comparison of the two texts it was identified that while Laban copied Klemm’s description of the minuet quite closely, he made slight changes, for example while Klemm referred to “der Herr” and “die Dame”, Laban changed this to “Person A” and “Person B”. This seems to indicate Laban’s purpose towards developing new modern dance forms, while also drawing on the tradition of popular dances in existence.

In a later interview with Valerie-Preston Dunlop [7], this theme of Laban’s development of “new dance” was continued where she gave an account of how Laban taught the minuet as part of a series of classes in dance history. She recounted how Laban considered traditional dance forms as examples of diversity and variety of movement qualities, for example primitive rhythmic dances displaying qualities of weight and time, and formal designs of ancient Egyptian dances revealing abstract geometric patterns such as tetrahedra. In the case of the minuet, this was considered as an example of refined spatial designs in time. In particular, she recounted how the minuet steps were taken as examples of three cardinal planes, which Laban referred to as the “door plane”, “wheel plane” and “table plane” (Fig. 1), specifically the minuet step right and minuet step left were taken as examples of the door plane, the minuet forward step taken as an example of the wheel plane, and minuet balance taken as an example of the table plane.

This account gives further indication regarding Laban’s process in development of a new modern dance and also of theories of human movement and methods for movement analysis. In other places Laban also describes more explicitly how he analysed existing dance and movement forms such as Feuillet notation [8] ballet [9], fencing or sabre fighting [10], and working movements [11], with the purpose of extracting core features and patterns of human movement, then incorporating these in development of theoretical models for human movement.

Characteristics of the three cardinal planes

As described, Laban drew concepts of the three cardinal planes from the minuet and these were continued to be explored, adapted, and refined in the development of methods for movement analysis, for example in the construction of “natural sequences and scales in space” in the system of “Choreutics” [12] or in the method of personal movement profiling known as “Action Profile” or “Movement Pattern Analysis” such as developed by Warren Lamb [13] . While in the minuet the movements are primarily with the legs, these are developed to also included movements of all parts of the body, further exploring potentials of the plane. Individual characteristics of the three planes can be explored in actual movement experiences.

Door plane

This plane is flat and like a wall. Sometimes it is also called the “vertical plane” or the “frontal plane”. It is possible to travel across the floor by moving in the door plane, but it is really not very good for this, but the plane is much better for movements that maintain the stance in place. From this stance it is easy to present oneself, make a gesture to be recognised or be seen. The door plan tends to organise relationships amongst people in patterns such as facing each other, or standing side-by-side in a line, everyone facing the same way.

Wheel plane

The plane is like a narrow passage tending to induce motions forward and back. Sometimes it is also called the “sagittal plane” or the “median plane”. Gestures in the plane are mostly pure flexion and extension movements and these readily lead into travelling across the floor in any direction, though mostly in straight lines. It is ideal for getting from point A to point B in the shortest distance. The wheel plane can organise relationships amongst groups of people in patterns such as in front and behind, or leading and following.

Table plane

The plane is like a flat surface parallel to the floor or the horizon and is also called the “horizontal plane”. Travelling movements are possible, but the plane tends to bring in characteristics of opening and closing, widening and narrowing, as well as twisting and untwisting that lead movements to changing directions and turning. The table plane can be used to expand outwards exploring large spaces, or also it is good for turning in to explore a personal inwards micro sphere. In relationships it is useful for opening outwards in order to then enclose another person inwards to oneself, or it can be just as useful for brushing someone to the side and away.

Different planes in interaction

The three planes can also be explored in interaction. A door plane might provide a stable stance for contacting movements from another person in a table plane. Movements in the wheel plane together with other dancers turning in table planes may create a whirl of travelling fluctuating revolving motion. Movements in a door plane can be useful for effectively stopping or catching some of the perpetual travelling in the wheel plane. People might have the personal preferences as to which plane they prefer in themselves and in others.

Body movement in the minuet analysed through Labanotation

Details of limb gestures and travelling in the minuet steps and their relation to the three planes can be analysed further by using the method of Labanotation. [14] Four notation scores of the minuet were examined. Labanotation scores of 17th century minuets are offered by Gisela Reber of the minuet from Gottfried Taubert, [15] and Reber together with Christine Eckerlie of the minuet from Pierre Rameau. [16] Inge Danker’s notation score represents a minuet of the 18th century from Kellom Tomlinson. [17] A Labanotation score by Irmgard Bartenieff, Kurt Jooss, Albrecht Knust and Gisela Reber presents a 19th century minuet from Bernhard Klemm. [18]

Comparison of these scores revealed many variations in minuet steps, their directions and rhythms, and the order of steps in longer sequences. Since Laban closely followed the description of the minuet by Klemm, and since the Labanotation score by Bartenieff and colleagues is explicitly named as being based on Klemm, it was selected as the best score for use in this analysis. It is also significant notators of this score were principal colleagues with Laban during the time of writing Choreographie, and so would have been intimately familiar with the role of the minuet in this work and so can be relied on for the best representation of his intent.

Basic minuet stepping rhythm

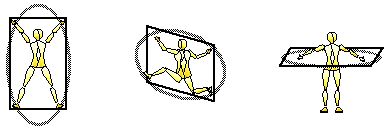

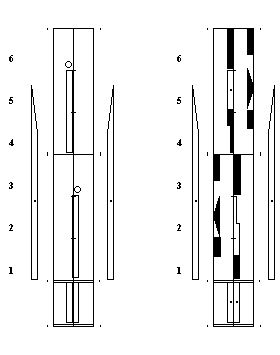

The timing for the rhythm of stepping in the minuet use here was drawn from the notation by Bartenieff and colleagues. Figure 2 shows the timing in the basic minuet stepping rhythm. This is represented in the Labanotation “staff” which was derived from the middle line in Feuillet notation, however in Labanotation this is regularised into a straight line with tick marks and bar lines for musical beats and measures, and expanded into separate columns for indicating supports and gestures of arms and legs. The rhythm of movement is written in these columns with “direction signs” which indicate duration of movement according to their length along the staff. In addition, a small circle in the staff indicates a “hold”, where the previous condition is retained.

Minuet steps right, left, and forward

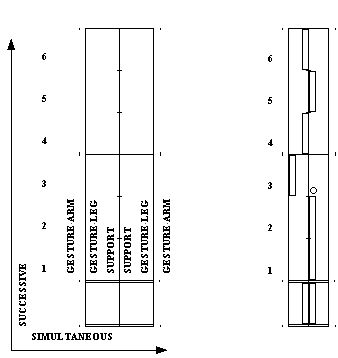

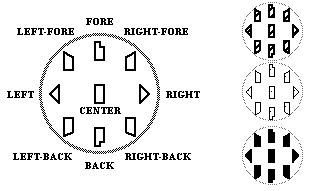

Directions for stepping and gestures are differentiated with the Labanotation direction signs with shapes that seem to point into particular directions, and are shaded to indicate level in space of high (hatched shading), middle (dot), or low (dark shading) (Fig. 3). Figure 4 shows minuet steps right, left, and forward which have the identical stepping rhythm. Directions and levels are shown with Labanotation direction signs, and additional “pins” are added when necessary to show if a step is placed just behind the other foot. The door plane in the minuet steps right and left is revealed by the sideways gestures and stepping with rising and lowering while the wheel plane in the minuet forward step is revealed by the forwards directions, also rising and lowering.

Minuet balance

Figure 5 shows the basic stepping rhythm for the minuet balance as well as the directions and levels of gestures and steps. As can be seen from the Labanotations, the stepping rhythm for the minuet balance is slightly different than that of the minuet steps right, left, and forward. Here, the balance consists of one slow step forward, followed by another slow step back. As shown in the shading of the direction signs, the stepping begins in low level (bent knees) and progresses to middle (knees straight), but never rise to high level (standing on toes). This detail is consistent in the Labanotation by Bartenieff and colleagues and would seem to reinforce the sensation of the table plane, since any motion up or down is minimal. Instead, the prominent features are the leg gestures which sweep sideways in a horizontal plane along the floor, together with raising of the arms opening outwards in preparation for contact with the partner. These features all reinforce a feeling of the table plane in the minuet balance.

Conclusions

Rudolf Laban appears to have drawn on the minuet as part of his process in the development of a new modern dance and methods of movement analysis and notation. Reference to the minuet would be natural for Laban in the early 1900s, when the logical thing to do would be to relate his development of dance methods to the currently practised dances and movement forms of the time. This research process was also typical of his method to consider traditional dance and movement forms such as ballet, sabre fighting and work movements, with an intention to identify fundamental characteristic movement patterns or organisations. The minuet was particularly highlighted as an example of refined spatial forms and design in which were identified occurrence of movement in three cardinal planes. These concepts continued to be developed in areas of study of space harmony where the three planes serve as a basis for sequential orders in movement “scales”, analogous to scales in music. [19]

Indeed, part of the reason for the longevity of the minuet over centuries of practical dancing, may include the choreography of the minuet as containing a series of transitions through sequences of all three cardinal planes, thus giving a full range of movement expressive possibilities. For example this might be contrasted with other dances such as the Galliard which is composed principally of movements in just one of the planes.

References