Organisations of chaos in an infinitely deflecting body-space

(2000) Jeffrey Scott Longstaff

HTML version of “Organisations of Chaos in an Infinitely Deflecting Body Space”.

Paper presented at A Conference on Liminality and Performance,

Brunel University Twickenham; 27-30 April 2000.

(Discussion: < http://www.dancetechnology.com/dancetechnology/archive/2000/0105.html > Retrieved July 2004)

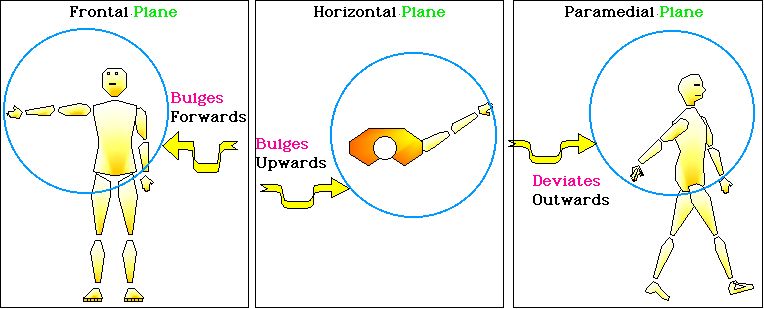

In traditional dance techniques and kinesiology body movements and positions are categorised according to Cartesian dimensions (vertical, lateral, sagittal), Cartesian planes (frontal, median, horizontal), and less frequently as 45º diagonals.

However, when we look in greater detail it is clear that body movements do not actually occur along pure Cartesian directions but tend to deflect into a virtually infinite variety of directions at odd, uneven, irregular angles to the Cartesian conception. These irregularly oriented directions can be identified as arising from five sources: 1) oblique joint structure; 2) oblique muscular lines-of-pull; 3) ranges of joint articulation; 4) physical momentum; and 5) desires for expressivity where Cartesian dimensions and planes are expressively flat, contained and restricted, whereas irregular orientations are expressive of dynamism, freedom, and liberation.

The same contrast is well identified in studies of spatial perception where features (visual lines, paths on a map, urban geography) are perceived and remembered as being more vertical, more horizontal or more along a pure 45° diagonal than they actually are. In the same way, angles are perceived and remembered as being closer to 90° than they actually are. This perceptual bias toward the dimensional or diagonal prototype is a typical effect also identified by Gestalt psychologists and is basic to theories of perception in visual arts where irregular orientations are perceived to be striving towards the more regular, symmetrical orientations.

Dimensions and diagonals are also evidenced as being most prototypical in language because of the greater number of specialised terms which have evolved to describe them, and this implicit bias in language is also evident in ballet-based dance terminology. Accordingly, pure Cartesian orientations are conceived to be the most fundamental and to serve as ‘reference points’ or heuristics (a general ‘rule of thumb’) for the perceptibility of other irregular orientations which allows complex chaotic spatial information to be perceived more easily and quickly.

This identifies the point of liminality in spatial perception, with the actual reality of infinite irregular and chaotic orientations tending to slip into the subliminal while the simpler, prototypical, symmetric, Cartesian orientations spontaneously emerge into perceptual experience and memory. To reach into the subliminal, to bring this into perceptual awareness and so to allow it to be mentally grasped, and thus consciously usable, requires some sort of systematic perceptual framework.

There are not any simple and well-known methods or terminologies for conceiving of these virtually infinite possible irregular spatial directions. One little-known method for movement conception emerged out of an artistic sub-culture in Europe during the 1920’s. According to Rudolf Laban’s conception of “deflections” the two prototypical sets of axes (3 pure dimensions and 4 pure diagonals) are set against each other as counter-acting tendencies. Within this conception, the infinite chaotic variations of irregular directions occurring during physical performance are each perceived as a relative orientation with both a dimensional and a diagonal component. That is, the spatial form is conceived as a diagonally deflected dimension or a dimensionally deflected diagonal.

Indeed, a movement action never occurs as identically the same from one execution to the next but the form and orientation will vary in a virtual chaos depending on the conditions present at each moment. Conceiving of deflections allows the infinite variety of physical movements to be perceived as oscillating or modulating between these two contrasting crosses of axes, the dimensional and the diagonal.

This is in agreement with models of motor memory and control, especially as identified by the famous Soviet cybernetics researcher N. Bernstein who characterised “the net of the motor field . . . as oscillating like a cobweb in the wind”.

This same method for allowing an organised perception of chaotic spatial variations can also be applied to perceptibility of qualitative dynamics in movement (eg. quality of force, of focus, of timing) where the contrasting tendencies are conceived as pure ‘mobility’ and pure ‘stability’, with their multitude of mixtures yielding the variety of dynamic qualities.

This conception of deflected bodily actions will affect the quality of movement perceptibility, which will in turn influence the physical experience and execution.

This expanded spatial conception also allows a leap of creative potential for generating new movement material well beyond the en croix of ballet.

In addition, and in as much as all cognition develops out of kinesthetic-motor experience, this is an expanded model for cognitive processes in general allowing for conceptions of events beyond limited over-simplistic Cartesian stereotypes of right and left (eg. as political positions), above and below (eg. in social hierarchy) and forward and backward (eg. as progress or retreat). Rather, the conception of deflections is a reach toward perceiving reality in its true infinite variety.

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 1

|

Organisations of Chaos in an Infinitely Deflecting Body Space

Jeffrey Scott Longstaff

A FUNDAMENTAL COMPONENT OF PERFORMANCE:

Spatial forms, designs, directions

produced by the human body

THIS RESEARCH CONSIDERS:

- Mental conceptions of the orientation of body spatial forms

- How these can influence body performance

------------------------------------------------------------------

Originally presented at:

“A Conference on Liminality and Performance”, Brunel University Twickenham; 27-30 April 2000.

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 2

|

|

ORIENTATIONS OF BODY MOVEMENTS ARE TYPICALLY ANALYSED IN

- Kinesiology

- Dance Technique

- Everyday Language

ACCORDING TO:

- Cardinal x, y, z cross of axes

- Three Dimensions

- Vertical, Lateral, Sagittal

- Three Cardinal planes

- Frontal, Horizontal, Medial

Less frequently:

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 3

|

|

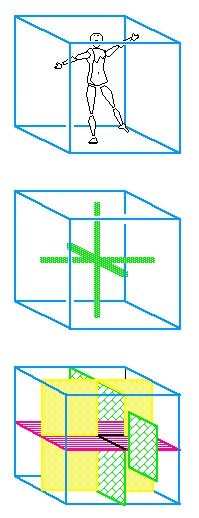

Ballet Technique

- Primarily Cartesian, Cardinal Conception,

- less frequently as diagonals (Kirstein & Stuart 1952; Lepczyk 1992)

|

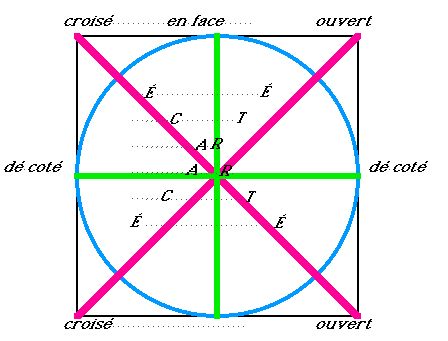

EG.

- Ballet ‘facing’ or

- “directions of épaulement”

Dimensional facings:

- facing the audience;

de coté - facing side of the room

45º Diagonal facings:

- legs crossed;

effacé or ouvert - legs open;

épaulée - front shoulder crossing the body;

écarté - leg wide to the side

|

“Personal square” for orientation of body facing

(adapted from Royal Academy 1991, 1)

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 4

|

|

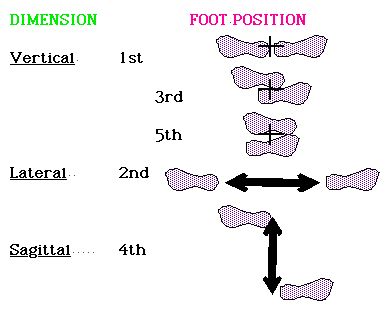

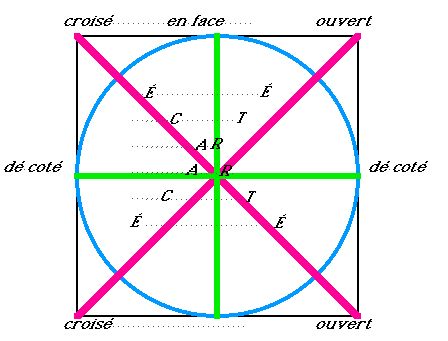

Ballet Technique

The Three Dimensions are embodied in the:

|

|

Five Positions of the feet

|

Orientation of Limb Positions

|

Dimensional conception evidenced in organisation of foot positions relative to the cardinal dimensions and the line of gravity

|

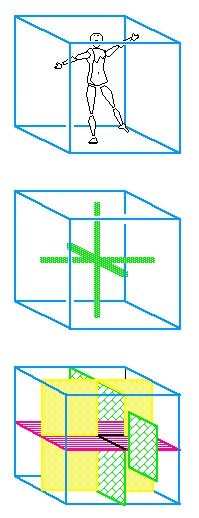

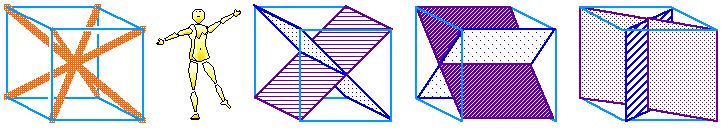

Dimensional conception in ballet is depicted in the “space module” or “theory of design”;

Dimensional lines superimposed over drawings of the human body

(Kirstein & Stuart 1952, 2, 20, 30, 81,104, 106)

Comprise a sort of three-dimensional expansion of the ‘personal square’ for facing.

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 5

|

|

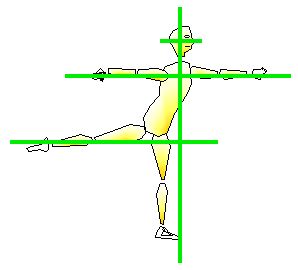

Ballet Technique

|

Orientations of limb positions and movements

Limb positions and motions are conceived primarily as Dimensional Orientations.

- room-relative motions:

- en avant or en descendant - stage-forward;

- an arriere or en reculant - stage-backward

- body-relative motions:

- devant - body-forward;

- derriere - body-backward

All room-relative diagonal directions:

|

Vertical components of limb orientation (height):

Orientations of the leg in the frontal or sagittal planes:

- In the initial distinction is determined by body structure, the leg orientation resulting according to how the foot is touching the floor:

- á terre - on the ground (exact angle not specified)

- en l’ air - in the air ( “ “ “ “ )

- When the foot is off the floor: “angle of the leg in the air”, “positions of the leg in the air”; “positions soulevées” - (raised positions)

- á la demi-hauteur - to the half-height, 45º

- á la hauteur - to the height, 90º

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 6

|

|

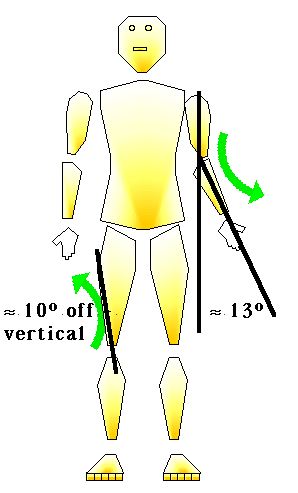

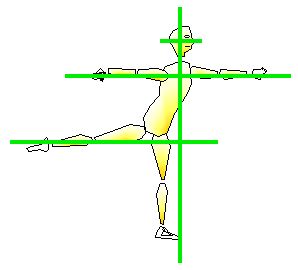

HOWEVER:

- Actual body movements do not occur in cardinal orientations,

- but deviate into an infinite variety of odd, irregular angles.

Sources of obliquely deflecting body motions:

Oblique joint structure

At the elbow, the articulatory surface of the humerus (trochlea) with the ulna is oriented at a “carrying angle” so that extending the forearm does not create a flat plane, but spirals outwards in an oblique motion relative to the humerus (Gray 1977, 257; Nordin & Frankel 1989, 251).

EG.

Knee articulation the tibia does not remain in a flat plane, but spirals outward into an orientation parallel with the femur (Gray 1977, 279).

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 7

|

|

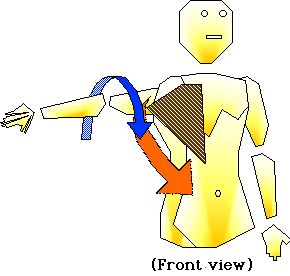

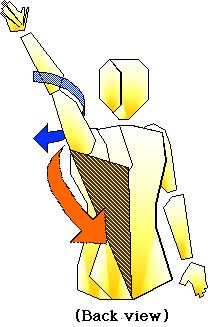

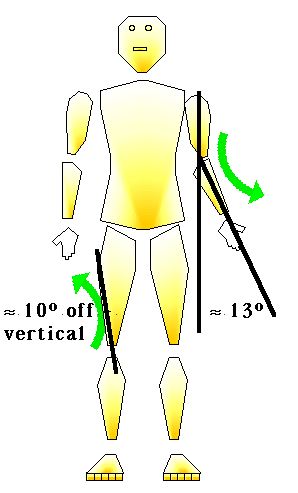

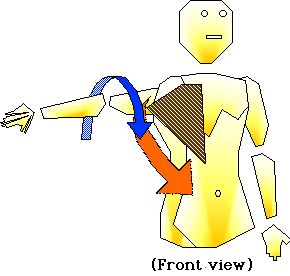

Oblique Muscular Lines-of-pull

Eg:

|

Pectoralis major;

- typically conceived as a horizontal planar flexor,

- also simultaneously adducts, and inward-rotates the humerus,

- moving a raised arm in an oblique motion down-forward-inward

(Gray 1977, 381).

|

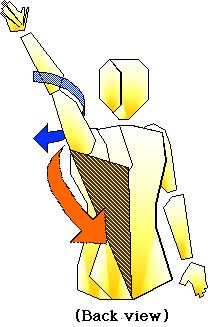

Latissimus dorsi;

- typically conceived as a frontal planar adductor,

- also simultaneously extends & inward-rotates the humerus,

- moving a raised arm in an oblique motion down-backward-inward

(Gray 1977, 341).

|

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 8

|

|

Joint Ranges of Motion;

- causes limbs to deviate out of purely flat planes, Eg:

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 9

|

|

Anatomical constraints:

- induce the well-known deviations in ballet away from Cardinal planes and dimensions:

Eg:

- 2nd Position of the gesturing leg deviates forward because of range of motion in the hip;

THUS: While

- Cardinal flat planes

are conceptually simpler

Oblique plastic planes are kinesiologically simpler

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 10

|

|

THIS SAME CONTRAST OF:

- Dimensional conceptual structure

(idea, memory, plan)

Deflected manifestation (embodiment, actual occurrence)

IS TYPICAL IN GENERAL SPATIAL COGNITION

|

THIS PROVIDES: "Cognitive economy":

A large amount of information is perceived & remembered

according to a small number of simple prototypes.

IE.

Perceptual/memory Reference points, or Heuristics (a rule of thumb)

- Information is perceived & and acted on faster,

- thus; Ecologically Advantageous (even at the expense of making small errors).

|

Spatial Terminology in Language

- indicative of which concepts are most fundamental:

GREATEST SPECIFICITY

- up, down, forward, back, right, left

Dimensions

high, deep, advance, retreat, widen, narrow

Planes; frontal, medial, horizontal

LEAST SPECIFICITY

- Diagonal, oblique, tilted

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 11

|

|

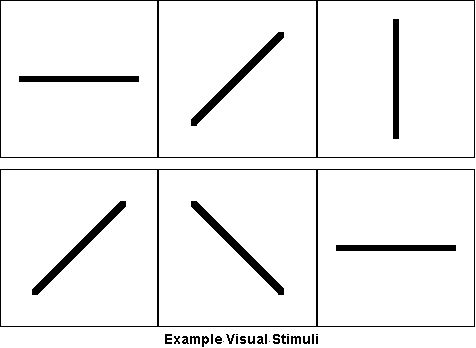

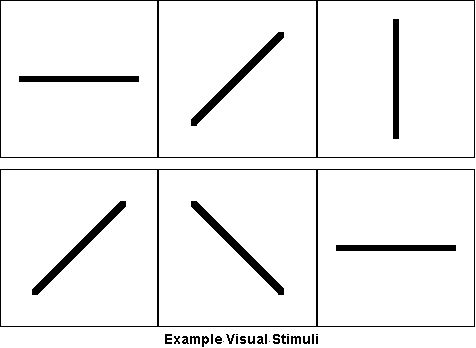

‘Oblique effect’ in perception

are perceived, recognised, learned, and responded to

more readily than diagonal lines.

|

EXAMPLE TASK:

Two buttons:

- press button 1 if the line is vertical or lateral

- press button 2 if the line is diagonal

Results:

Quicker Reaction Time to Vertical and Lateral lines (measured in thousandths of a second)

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 12

|

|

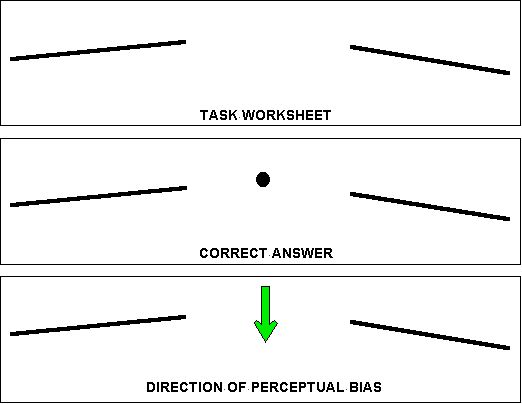

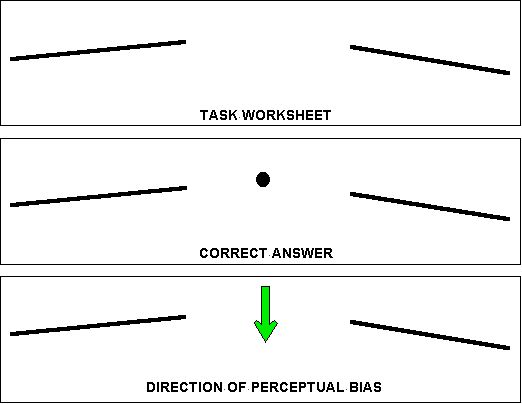

Perceptual & memory bias toward dimensional orientations

- Spatial forms are perceived / remembered as more dimensional than they actually are.

|

EG.

Estimating Converging Line Segments

TASK:

Place a dot where the lines would intersect.

RESULT:

The dot is placed as if the lines were more lateral or vertical than they actually are

(Weintraub & Virsu, 1971; 1972).

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 13

|

|

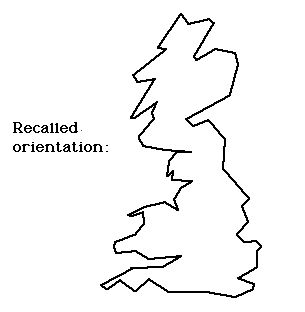

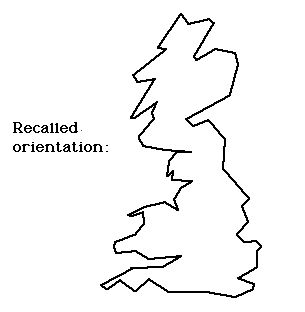

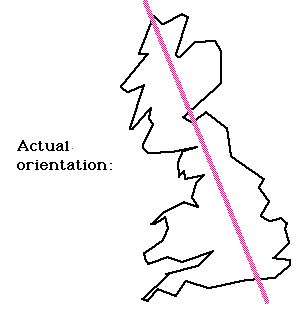

Memory Bias toward Dimensional Orientations

Drawing maps from memory (small neighborhoods, cities, countries, continents, make–believe maps)

- directions are recalled closer to vertical or lateral orientations (north/south; east/west)

- than they actually are

(Moar 1978; Tversky 1981)

TASK: Draw the British Isles.

- The long axis tends to be remembered as lining-up with the north/south axis,

- more than it actually does (approx. 20º northwest/southeast)

(Moar 1978, 92).

|

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 14

|

|

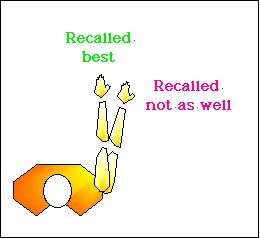

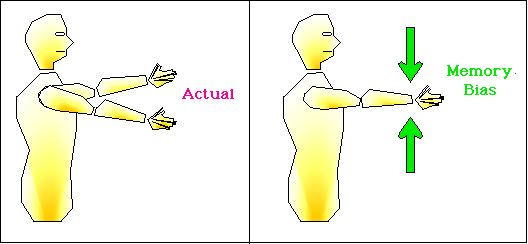

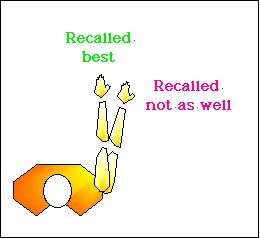

Perceptual & memory bias toward dimensional orientations

Recall of Body Positions:

- Recall of Sagittal arm position is more accurate than

- recall of positions just right or left of forward

(Wyke 1965).

|

|

|

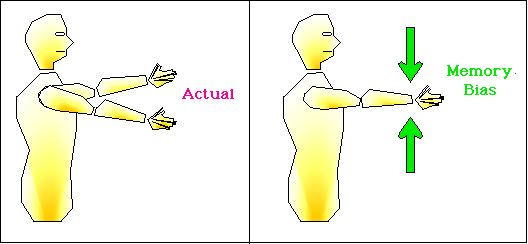

Memory Bias toward dimensional position

- after 24 hour memory interval

- arm position recalled as more dimensional than actuality.

(Clark & Burgess, 1984)

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 15

|

|

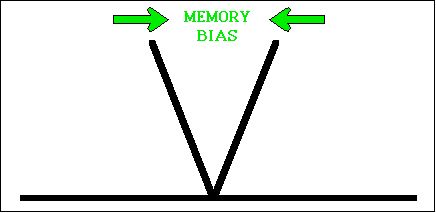

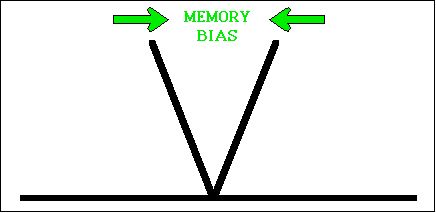

Perceptual & memory bias toward right and straight angles

- Angles are perceived/remembered as closer to right angles or straight angles

- than they actually are.

|

TASK:

- Draw the intersections between pairs of roads, or

- draw the directions towards two landmarks, in a well-known city

(Byrne 1979; Moar & Bower, 1983).

RESULTS:

- For angles between 60-80 degrees

- recalled closer to 90 degrees (right angle) than actually

|

|

|

This same effect was observed by Gestalt psychologists where (Eg.)

- an 85º angle, presented very briefly,

- is perceived as an impure Right angle

(Wertheimer 1923, 79).

They developed FUNDAMENTAL PERCEPTUAL PRINCIPAL of:

“Pragnanz” = Perception tends to be as simple, concise, and regular as possible.

Dimensions & 45º diagonals, and straight & right angles

are the most ‘Regular’ orientations and angles.

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 16

|

|

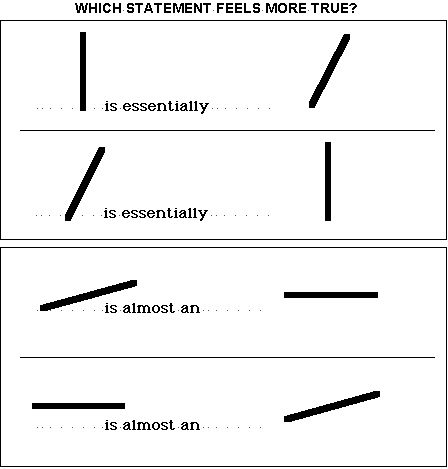

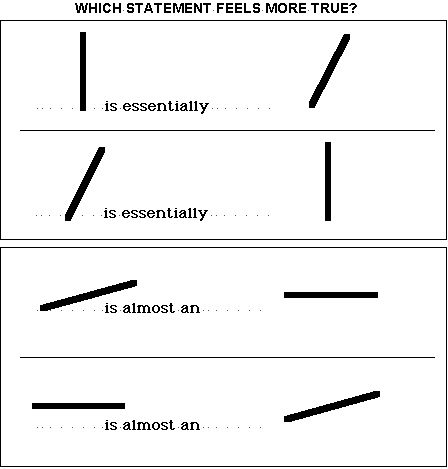

CONCEPTUALLY FUNDAMENTAL ORIENTATIONS

TASK:

- Given two lines in different orientations,

- insert into Linguistic ‘Hedges’

Results:

- vertical, horizontal and 45º diagonal orientations all served as

- reference points for other irregular orientations

(Rosch 1975).

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 17

|

|

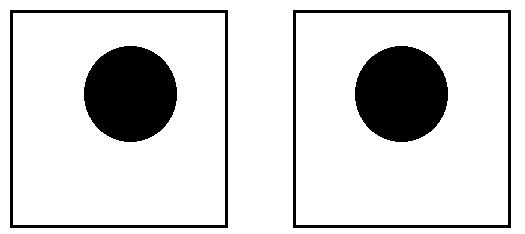

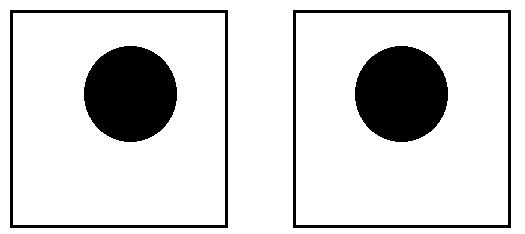

Perception of visual arts

Effects from spatial orientation in Perception of Visual Arts (Arnheim 1974)

: most stable

45º diagonal orientations less stable, more dynamic

irregular tilted orientations Most dynamic, potential energy, appear to strive toward a dimensional situation

EG. A black disk in a square appears to move toward a dimensional or diagonal placement

(Arnheim 1974, 11-14)

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 18

|

|

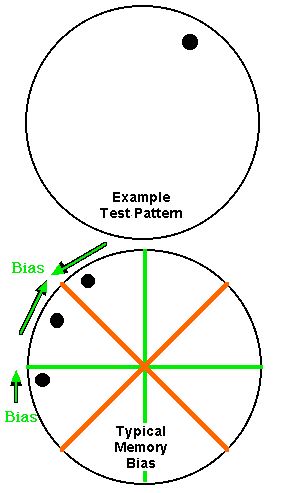

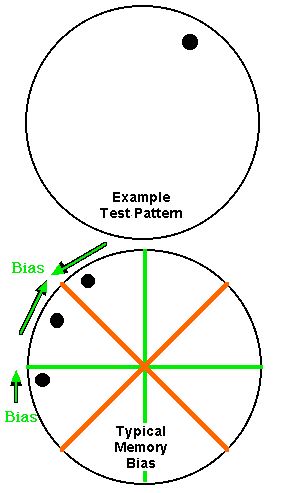

Perceptual/Memory Bias

TASK:

- Recall the location of a Dot in a circle.

RESULTS:

- Memory bias toward Dimensions and 45 degree Diagonals

“Subjects spontaneously impose horizontal and vertical boundaries that divide the circle into quadrants. They misplace dots toward a central (prototypic) location in each quadrant” (Huttenlocher et al. 1991).

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 19

|

|

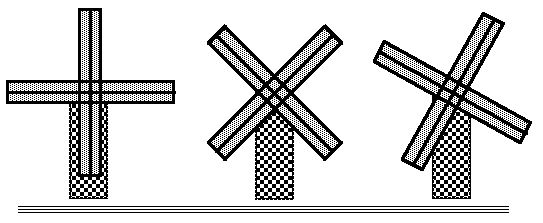

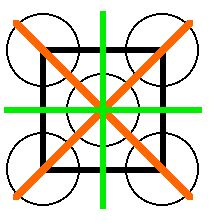

Patterns of Perceptual Bias.

A “structural skeleton” gives a map of how memories / perceptions are drawn towards “basins of attraction & repulsion”

(Arnheim, 1974, 11-16)

|

Eg.

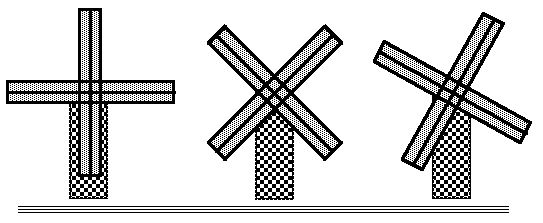

Perception of dynamics in Orientation of Windmills.

- Perceived motion in windmills

- appear to be drawn or pulled towards regular orientations.

(Arnheim 1974, 425)

- regular dimensions and pure diagonals: Most Stable - Least perceived Motion

- irregular obliques and tilts: Least Stable - Most perceived Motion

|

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 20

|

|

v SUMMARY: Body-spatial cognition:

- MENTAL IMAGE: concise, regular

PHYSICAL ACTION: deviating, irregular, chaotic

Even ‘the same’ movement (in your mind)

will manifest at least slightly differently (in reality) on each new occurrence.

The mapping of this virtual chaos is characterised in motor control as:

“The net of the motor field . . . as oscillating like a cobweb in the wind”

(Nikolai Bernstein, 1984, 109)

|

|

v WHAT IS NEEDED:

- A method of analysis which can bring manifestations of irregular orientations into greater perceptual awareness

|

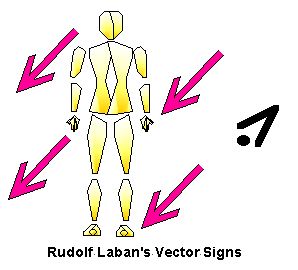

v ONE POSSIBILITY CONSIDERED HERE:

- Concept of Deflections

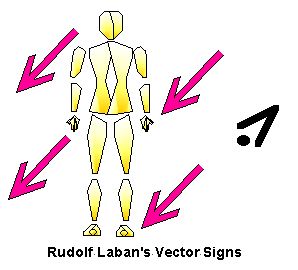

- System of Choreutics (Rudolf Laban, 1926; 1966)

- Especially revealed in an early method for Movement Notation (Laban 1926)

Two Characteristics for Organising infinite variations in body space:

- VECTORS: - Infinite Locations / Placement

- DEFLECTIONS: - Infinite Orientations

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 21

|

|

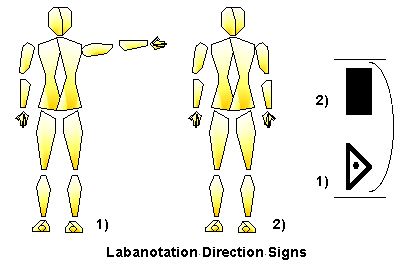

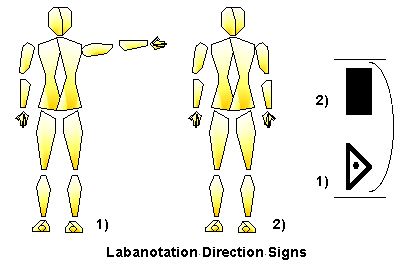

VECTORS: Infinite Locations / Placement

|

TYPICAL CONCEPTION OF MOTION:

- Position -to- Position: point-to-point

EG.

- Arm pose rightwards;

- Arm pose downwards:

Indicates movement: implicitly

|

‘VECTOR’ CONCEPTION OF MOTION

- Orientation of line-of-motion

EG.

- Arm motion down-back-leftwards;

Indicates movement Explicitly

|

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 22

|

|

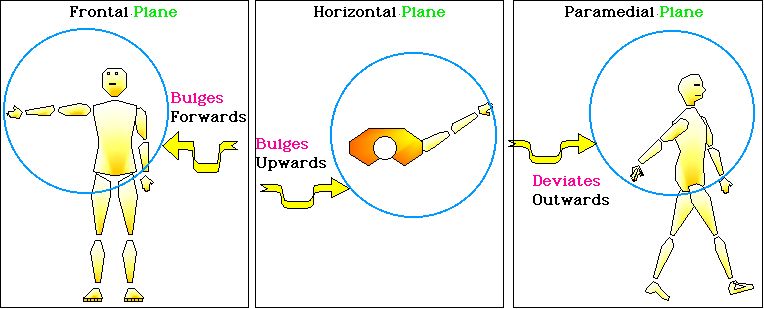

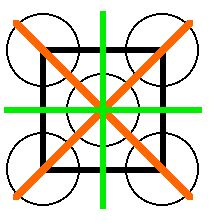

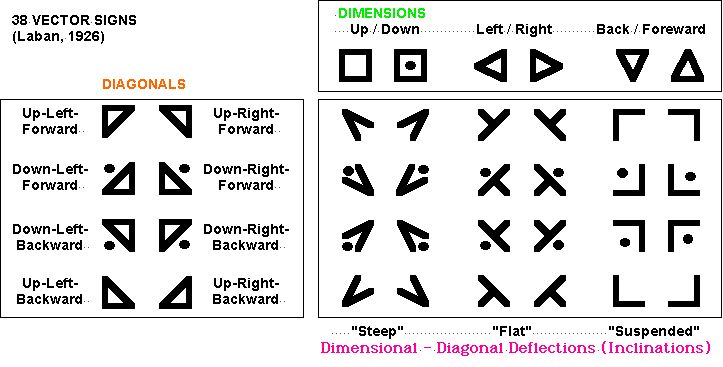

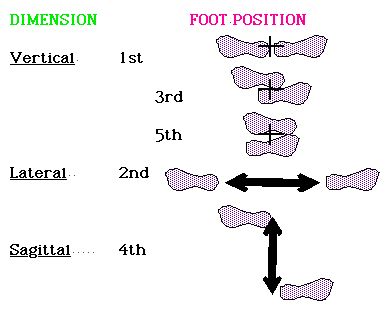

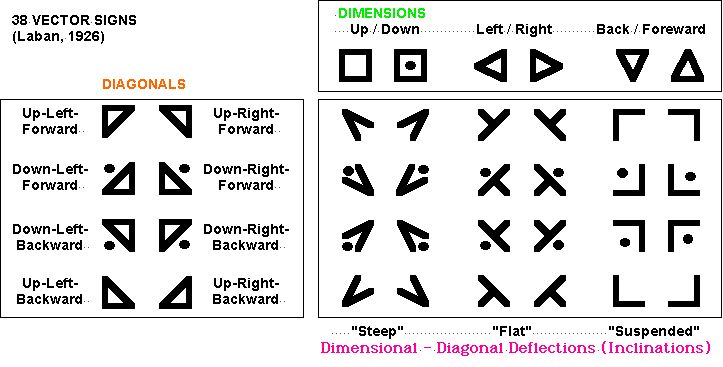

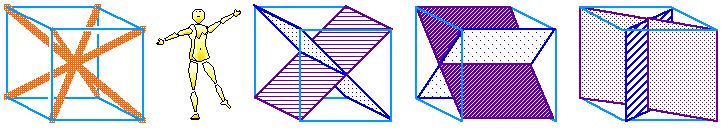

DEFLECTIONS: Infinite variety of Orientations

- Each of 8 Diagonal Directions

- Are deflected by each of 3 Dimensions:

- Producing ach of 24 Dimensional / Diagonal Deflections (Inclinations)

|

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 23

|

|

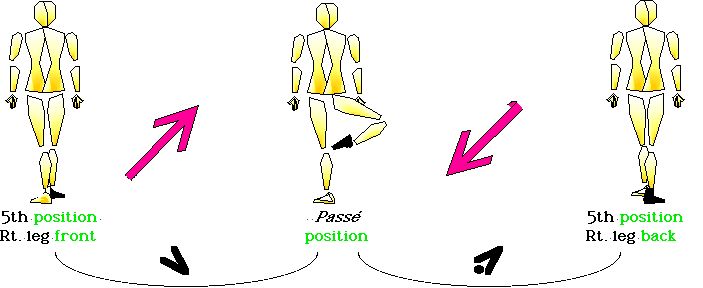

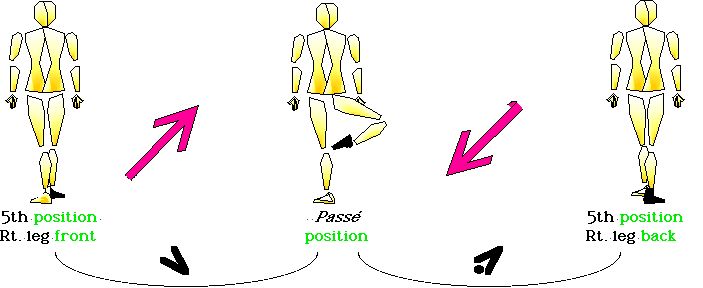

Re-envisage dance technique

- Deflected content of codified ballet technique can be identified in the

- transition from position to position (part of Laban’s 1926 analysis)

EG: Simple moves: Passé

|

|

|

Motion of leg c.g.

- up- - - - hip flexion

- right- - - away from midline

- back- - - - weight shift back

|

Motion of leg c.g.

- down- - - hip extension

- left- - - towards midline

- back- - - weight shift back

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 24

|

|

Re-envisage dance technique

Orientation method provides more possibilities for Spatial Inventiveness

TYPICAL DANCE CONCEPTION

- 3 Dimensions (6 directions)

- 3 Cartesian planes

- Attempt to minimise deflections

DEFLECTING DIAGONAL CONCEPTION

- 4 Diagonals (8 directions)

- 6 Oblique planes

- Identify and utilise deflections

|

|

Organisations of Chaos. (2000) J.S.Longstaff p. 25

|

|

SUMMARY: SIGNIFICANCE

Mental conceptions influence Perceptual Experience

- Frame perceptual experience relative to memory schemata (conceptual prototypes).

- Guide perceiver towards ‘obtained’ perception; (Seek-out perceptual data according to what is expected.)

|

Re-envisage movement techniques (as above)

|

Expand expressive spatial metaphors which model mental conceptions

EG. dimensional conceptions

- Right / Left (political ideology)

- Above / Below (social hierarchy & dominance; class structure)

- Forward / backward (rank order or priority)

Conceiving of deflections can encourage spatial metaphors away from narrow simplistic stereotypes, and towards the actual manifestations of infinite variety.

|

REFERENCES

- Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and Visual Perception; The New Version. (expanded and revised) Berkeley: University of California Press. (Originally 1954)

- Appelle, S. (1972). Perception and discrimination as a function of stimulus orientation: The “oblique effect” in man and animals. Psychological Bulletin. 78 (4): 266–278.

- Attneave, F., and Olson, R. K. (1967). Discriminability of stimuli varying in physical and retinal orientation. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 74: 149-157. [oblique effect]

- Attneave, F., and Reid, K. W. (1968). Voluntary control of frame of reference and slope equivalence under head rotation. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 78 (1): 153–159. [oblique effect]

- Bartenieff, I., and Lewis, D. (1980). Body Movement; Coping with the Environment. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Beery, K. E. (1968). Estimation of angles. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 26; 11-14.

- Bernstein, N. (1984). The problem of the interrelation of co-ordination and localization. In Whiting, H. T. A. (Ed.) Human Motor Actions; Bernstein Reassessed. New York: North Holland. (Originally published 1935; also published in The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1967.)

- Bodmer, S. (1979). Studies based on Crystalloid Dance Forms. London: Laban Centre.

- Byrne, R. W. (1979). Memory for Urban Geography. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 31; 147-154.

- Camisa, J. M., Blake, R., and Lema, S. (1977). The effects of temporal modulation on the oblique effect in humans. Perception. 6: 165-171.

- Clark, F. J., and Burgess, P. R. (1984). Longterm memory for position. Unpublished manuscript, Dept. of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Nebraska College of Medicine: Omaha. (Reviewed in Clark and Horch 1986, p. 26).

- Clark, F. J., and Horch, K. W. (1986). Kinesthesia. In Handbook of Perception and Human Performance; Volume 1, Sensory Processes and Perception, edited by K. R. Boff, L. Kaufmann, and J. P. Thomas (pp. 13.1-13.62). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Dempster, W. T. (1955). The anthropometry of body action. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 63:4; 569-570.

- Gray, H. (1977). [Grey’s] Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical. Revised American from the 15th English edition. New York: Bounty Books.

- Green, M. (1986). Mountain of Truth; The Counterculture Begins, Ascona, 1900-1920. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

- Hollerbach, J. M. & Flash, T. (1982). Dynamic interactions between limb segments during planar arm movement. Biological Cybernetics. 44.

- Hutchinson-Guest, A. (1983). Your Move: A New Approach to the study of Movement and Dance. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Huttenlocher, J., Hedges, L. V., and Duncan, S. (1991). Categories and particulars: Prototype effects in estimating spatial location. Psychological Review. 98:3; 352-376.

- Kapandji, I. A. (1970). The Physiology of the Joints; Vol. 1. Upper Limb. Translated by L. H. Honoré. 2nd edition. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone.

- Kirstein, L., and Stuart, M. (1952). The Classic Ballet. (Twenty-second printing 1986) New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Laban, R. (1926). Choreographie. Jena: Eugen Diederichs.

- Laban, R. (1966). Choreutics, annotated and edited by Lisa Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans.

- Loftus, G. R. (1972). Eye fixations and recognition memory for pictures. Cognitive Psychology. 3: 525-521.

- Longstaff, J. S. (1996). Cognitive Structures of Kinesthetic Space. PhD Thesis: Laban Centre London; City University.

- Longstaff, J. S. (1999). Vectors and deflections in Laban’s Choreographie. In I. Bramley (Ed.), Theorising and Contextualising Dance; Papers from the Laban Centre Research Day (pp. 43-51). London: Laban Centre.

- Lynch, K. (1960). The Image of the City. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

- MacLean, I. E., and Stacey, B. G. (1971). Judgement of angle size: An experimental appraisal. Perception & Psychophysics. 9:6; 499–504.

- Matin, E., and Drivas, A. (1979). Acuity for orientation measured with a sequential recognition task and signal detection methods. Perception & Psychophysics. 25 (3): 161-168. [oblique effect]

- Moar, I. (1978). Mental triangulation and the nature of internal representations of space. St. John’s College Cambridge: Ph.D. diss.

- Moar, I., and Bower, G. H. (1983). Inconsistency in spatial knowledge. Memory & Cognition. 11:2; 107-113.

- Nordin, M. & Frankel, V. H. (1989). Basic Biomechanics of the Musculoskeletal System. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

- Piaget, J. & Inhelder, B. (1967). The Child’s Conception of Space. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Preston–Dunlop, Valerie. (1984). Point of Departure: The Dancer’s space. London: Published by the Author, 64 Lock Chase SE3.

- Rasch, P. J. & Burke, R. K. (1978). Kinesiology and Applied Anatomy, 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

- Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive reference points. Cognitive Psychology. 7; 532-547.

- Royal Academy of Dancing. (1991). Grades examinations syllabus; pre-primary to grade 2. London: Royal Academy of Dancing.

- Salter, A. (1977). The Curving Air. London: Human Factors Associates.

- Tversky, B. (1981). Distortions in memory for maps. Cognitive Psychology. 13; 407-433.

- Ullmann, L. (1971). Some Preparatory Stages for the Study of Space Harmony in Art of Movement. Surrey: Laban Art of Movement Guild.

- Weintraub, D. J., & Virsu, V. (1971). The misperception of angles: Estimating the vertex of converging line segments. Perception & Psychophysics. 9:1A, 1971; 5-8.

- Weintraub, D. J., & Virsu, V. (1972). Estimating the vertex of converging lines: Angle misperception? Perception & Psychophysics. 11:4; 277-283.

- Wertheimer, M. (1923). Laws of organization in perceptual forms. Reprinted in Ellis, W. D. (Trans. & Ed.) A Source Book of Gestalt Psychology, (4th edition 1969). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Wyke, M. (1965). Comparative analysis of proprioception in left and right arms. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 17: 149–157.

- ----------------------------------------