A kinespheric “pose” refers to the positions of the body’s physical mass. This is also referred to as a “body design” (Preston-Dunlop, 1984, p. x;) or a “limb constellation” (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, p. 180). A variety of kinespheric pose categories have been distinguished in choreutics and dance studies. These can be refined by conceptions of body poses in spatial cognition research.

IVB.21 Pin-, Wall-, Ball-, and Screw-shaped Poses.

Laban (1980, p. 63) distinguished four types of “body carriage and its shape” according to the “structural and functional factors of the body”: 1) “Pin-like” shapes arise from the “spine and its pin-like extension”; 2) “wall-like” shapes arise from a flat surface created by the “right-left symmetry of the body”; 3) “Ball–like” shapes arise from the “curling and circling” of the limbs together with the trunk; 4) “Screw-like” shapes arise from the “shoulder-girdle and the pelvis twisted against one another”.

Other authors adopted these four categories of kinespheric poses. Preston–Dunlop (1980, pp. 90-92) begins with two more fundamental categories of poses, “large” body shapes which are “done by the whole body” and “small” shapes which are “done by smaller parts” of the body. Pin-like shapes are conceived to be variants of the large shape and consist of an “elongated” “‘line from head to foot’” which “penetrates the space”. Wall-like shapes are also variations of the large shape. They are “spread out” and “flat” in which “the limbs extend away from one another in two dimensions, with the centre of the body as the hub” and have a character of “dividing the space”. Ball-like shapes are derived from the small shape. They consist of “curling up” in which the “whole body, and in particular the spine, rounds itself” while the limb extremities “try to meet and merge” and have a character of “surrounding the space in concave positions or displacing it in convex positions”. Screw-like shapes are derived from a mixture of the small and large shapes in which “the extremities of the body pull against one another . . . in different directions around an axis” so that the different body-parts are “twisting away from one another”.

Bartenieff and Lewis (1980, p. 110) refer to these four poses as “body attitudes”. The pin shape is “straight and narrow” and penetrates space. The wall shape is “straight and spread” and divides space. The ball shape is “rounded” and surrounds or fills space. And the screw shape consists of the “upper body twisted against [the] lower” and is “winding” in the space.

IVB.22 Straight, Curved, and Angled Poses.

Preston-Dunlop (1981, p. 44) presents an analysis in which all poses are classified as either straight or curved. The modern dancer Doris Humphrey (1959, pp. 49-58) referred to body poses as “static line” and categorised these as either “oppositional”, that is “opposed, in a right angle” and expressing maximum power, or “successional”, that is “flowing, as in a curve” and expressing gentleness “in curves or straight lines”. Thus, while Preston-Dunlop distinguishes between curved and straight categories of poses, Humphrey categorises curved and straight into the same category and distinguishes a separate category for angles.

IVB.23 Arabesque and Attitude Poses.

In the ballet tradition two general categories of body poses are distinguished. Grant (1982) defines the arabesque as “one of the basic poses in ballet” in which the body stands on one leg with the other leg extended and “the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line from the fingertips to the toes”. Many variations are possible within this category of poses since “forms of arabesque are varied to infinity” (p. 2). The attitude pose was derived from the statue of “Mercury by Giovanni da Bologna” (p. 9). In this category the gesturing leg and arms are bent so that they appear to be gently curved. Thus the arabesque and attitude categories of poses in ballet are essentially categories of straight versus curved poses.

IVB.24 Poses Arranged in Geometric Networks.

In the choreutic tradition, and also in art and architecture, kinespheric poses are often conceived according to their relationship to an imaginary polyhedral or polygonal network. This is essentially a mapping of poses relative to the nodes of a conceptual kinespheric network. A variety of networks have been used such as squares, rectangles, pentagons, and pentagrams in various orientations. An unique contribution of choreutics its its use of various polyhedra for conceptual kinespheric networks. These have been introduced in earlier sections (IIIC.30) and analysed in greater detail (IVA.20).

IVB.25 Counterdirections and Chords.

In the choreutic tradition a pose which consists of an arrangement of at least three limbs can be referred to as a “chord” (in the musical sense) (Preston-Dunlop, 1984, p. x), a “chordic interrelationship of the three limbs”, as “triadic chordic constellations”, or as a “chordic tension” (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, pp. 107-108, 116, 193).* The limbs within the chord may be oriented to that they equally balance each other and provide an overall equilibrium to the body (see IIID.50). This 3-part equilibrium chord is a plastic version of the equilibrium created by the 2-part “countertension” or counterdirection in which limbs are oriented into two opposite directions (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, pp. 103-108, 114).

__________

* A chord is sometimes referred to as “chordic countertension” which has only two opposing directions (Bartenieff and Lewis, 1980, p. 116; Preston-Dunlop, 1984, p. x) but this would seem to dilute the meaning of a 3–part “chord” versus to “counter” which typically refers to two elements in direct opposition. If used in a musical analogy a “chord” will refer to three or more simultaneous elements.

__________

IVB.26 Kinespheric Pose Primitives: The Body Segment.

Conceptions of kinespheric poses are based on the physical structure of the body. The skeleton gives the body its structure. Other tissues add to this structure but the skeleton determines the overall shapes that the body can create. Therefore, all poses will have the structure of the skeleton at their basis.

Bones have a variety of shapes which include bulges on their surfaces, spirals within bony structure, flat and curving bones of the scapula and skull, curved ribs, and the S-shaped curve of the vertebral column. Nevertheless, most bones which give the body its form have an overall straight shape. these straight segments of the skeleton can be referred to as “body segments”. Categories of kinespheric poses must necessarily be based on an arrangement of straight body-segments.

Marr and Nishihara (1978; Marr, 1980) identify the straight body segment as the primitive component in the visual representation of body poses. They point out that an object (eg. an animal’s body) has a “natural decomposition into components” which each exhibit a “principal axis of elongation or symmetry”. The longest dimension of a form will tend to be assigned as the principal axis along which the figure will be remembered (also noted by Attneave, 1968; Rock, 1973, p. 38). Each elongated axis becomes a line within a “stick figure” representation of the body. The easy recognition of an animal’s body from stick figure drawings indicates that the straight segments of the stick figure are the essence of the mental representation of the body structure (Marr, 1980, p. 211). The stick figure can be conceived at different levels of detail so that there is a “hierarchy of stick-figure specifications”. At the highest level a single line represents the entire body along its most elongated axis. At the next level each limb and the spine is represented with a single line along their lengthwise axes. Through progressive levels of detail, smaller and smaller body-segments are specified with an individual line in the stick-figure.

This same cognitive structure is evident in Labanotation symbols for body–parts. A single symbol can be used to represent an entire limb or the entire torso. Variations of the full-limb symbols are then used to refer to lower-order parts of the limbs (Hutchinson, 1970, pp. 248, 317).

IVB.27 Gestalt Principles of Higher-Order Perceptual Groupings.

Poses are not typically perceived as individual body segments. They tend to be spontaneously organised into higher-order groupings which are then perceived as curved, spiraled, figure-8, tetrahedral etc. poses. The question for an objective analysis is: What factors contribute towards certain higher-order groupings being perceived?

Certain principles have been identified which describe how various types of stimuli tend to be perceptually organised into higher-order groupings. Gestalt psychologists referred to the fundamental factor as the law of “pragnanz” (Koffka, 1935, p. 110). This is literally translated from German as “concise” or “terse” (Collins, 1969) which are defined as “neatly brief” and “expressing much in few words” respectively (Collins, 1986). Koffka (1935, pp. 108-145) and Wertheimer (1923, pp. 79–83) describe pragnanz as organized groupings of stimuli which are the most “good”, “regular”, “simple”, “stable”, “logically demanded”, with “inner coherence”, “inner necessity”, “wholeness”, and that within each element exist the principle of the whole group of elements. They hypothesize that perceptual processes will always organize the stimuli to be as “good” (ie. according to pragnanz) as the conditions will allow. More specific manifestations of pragnanz were identified (Koffka, 1935, pp. 148-171; Wertheimer, 1923, pp. 75-87):

According to “proximity” when stimuli are near to each other in time or space they tend to be grouped together relative to more distant stimuli.

According to “similarity” (called “equality” by Koffka, 1935, p. 165) when stimuli have a similar shape, colour, orientation etc. as each other they tend to be grouped together relative to other more dissimilar stimuli.

According to “continuation” (called “direction” by Wertheimer, 1923, p. 80) a continual series of stimuli (eg. a row or a column of separate objects) will tend to be grouped together as a single unit. A continuation of a straight line maintains its direction and a curved line maintains its curvature.

According to “closure” if a collection of stimuli completes, or nearly completes, a circuit which encloses space, this entire area will tend to be grouped together as a single unit.

According to “common fate”, stimuli which are moving at the same time, in the same direction, or traveling the same distance, tend to be grouped together as a single unit.

According to “unum and duo” (Koffka, 1935, p. 153) a stimuli configuration will be perceived as one figure, or perceptually divided into two or more sub-figures, depending on which of these groupings arranges the stimuli into figures which exhibit the greatest amount of simplicity and symmetry.

In many cases these principles of organisation all work together in agreement to derive a particular grouping of the stimuli. In other situations the principles may be in conflict and so, for example, an organisation according to proximity might dominate a different organisation which would have occurred according to similarity.

The causes of pragnanz can be discussed according to the Nature versus Nurture debate:

Gestalt laws of perceptual organisation make reasonable intuitive sense, but they are obviously descriptive statements possessing little or no explanatory power. The Gestaltists appear to have believed that their laws reflected basic organisational processes within the brain [ie. Nature], but it is much more plausible to assume that the laws arise as a result of experience [ie. Nurture]. It tends to be the case that visual elements which are close together, similar, and so on, belong to the same object, and presumably this is something which we learn. (Eysenck and Keane, 1990, p. 58)

The overall Gestalt principal of pragnanz describes how perceptual and cognitive processes attempt to group stimuli into the simplest, most concise, most symmetrical manner possible. This provides a great deal of cognitive economy and so is a beneficial strategy for an organism, even at the risk of remembering stimuli as more concise than they actually were. This is a type of perceptual bias related to the perception of prototypes (see IVA.32).

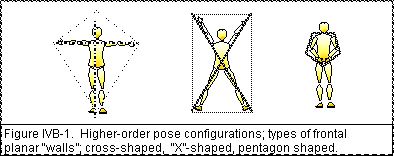

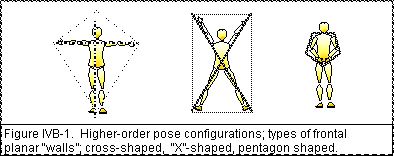

In the perception of kinespheric forms if many body segments are aligned in a straight line these may be organised into a single higher-order unit according to the Gestalt principles of continuation, similarity, and unum-duo. An arrangement of straight body segments can be made even more concise by organising them into even higher-order units such as an “X”–shape, a cross, or a pentagon (which also includes the Gestalt principle of closure) (Fig. IVB-1). Likewise, if several body-segments are arranged in a series of similar sized angles these may be organised into a single higher-order curved pose according to Gestalt principles of continuation, similarity, and unum-duo. When the ends of body-segments are almost touching each other the curve may be perceived to connect across the empty space to form an entire circle according to the principles of closure and proximity (Fig. IVB-2).

The angles between body segments leading to the perception of curved versus angled poses may be derived from a series of body segments which all have similar sized angles, or from a performer’s dynamics (eg. relaxed versus tensed muscles). Perception of the pose as a pin, wall, ball, screw, or any other descriptive over-all shape occurs through this automatic process of perceptual grouping. These higher-order groupings provide the most concise description and economical mental representation of a kinespheric pose.